A. Introduction

What Is a Livable and Sustainable Community?

Green, sustainable and livable were aspirations that were expressed during the Comprehensive Plan community visioning process and were incorporated into the Vision Statement and Guiding Principles.

Livable may be subjective for each citizen, but it has been defined as a quality of life standard that is attached to a place. Kirkland as a place needs to have characteristics that allow it to be connected, be aesthetically pleasing to be in and allow access to the basic needs of living such as clean water, air, healthy food, affordable housing, education, and employment opportunities. A livable city should also have reliable infrastructure including government that is proactive and can manage its operations to ensure that the quality of life stays high for a majority, if not all, of its citizens. The concepts of livable and sustainable go hand in hand.

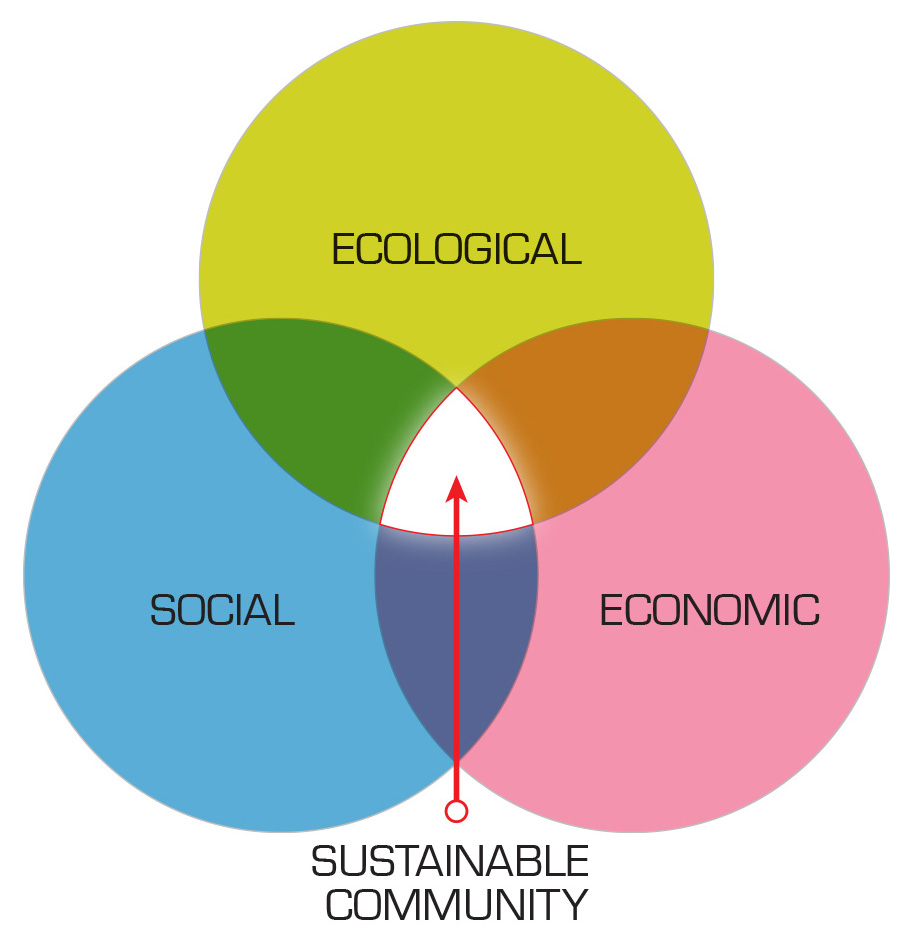

Sustainability means meeting our present needs while ensuring future generations have the ability to meet theirs. To become a more sustainable city, we need to consider the long term and wide ranging impacts of our actions and to evolve, strengthen and expand our policies and programs to adapt to new situations. The three key areas of sustainability are:

• Ecological Sustainability: Ensure that natural systems and built structures protect habitats, create a healthy environment, and promote energy efficiency.

• Economic Sustainability: Ensure a strong economy that is able to support our community while not compromising the environment in which we live.

• Social Sustainability: Ensure that we provide a sense of community to our residents, and support basic health and human service needs.

Resilience takes sustainability to the next step in which a community can adapt to the ever changing environment in a socially responsible manner. At its most basic level, a resilient community ensures that its residents and workforce can provide food and water during extreme weather events or disasters. In the built environment, it means encouraging buildings that have a low carbon footprint and thus do not impact the environment, such as the recently completed Bullitt Center building in Seattle. This building harvests its energy from solar panels, collects rain water for nonpotable uses, and processes all its sewage waste internally. The Center is an example of a self-sufficient living building constructed according to the International Living Future Institute’s standards.

Solar Panel House

What components of a livable and sustainable community do we have now?

The Growth Management Act requires the City to adopt development regulations that protect critical areas. For Kirkland, these include wetlands, frequently flooded areas, fish and wildlife conservation areas and geologically hazardous areas. Kirkland has codes, laws, policies and programs in place now to protect the natural environment such as our streams, wetlands, and lakes to certain standards.

However, when development is proposed near these sensitive areas, the buffers for development will need to be evaluated to provide a greater level of protection necessary to maintain their function and values and ensure restoration of these natural systems and their important ecological functions. In some cases our natural systems such as streams have been altered or placed in underground pipes prior to regulations being enacted that may have protected them. The State’s Best Available Science standard is to be used in updating the City’s critical area regulations.

The intent of Kirkland’s tree code is to maintain and enhance the City’s overall tree canopy in order to maximize the public benefits provided by trees. When initially drafted, the code aimed to increase the Citywide tree canopy cover to 40 percent. Having met the canopy goal – a measure of quantity – the City is shifting its focus to urban forest quality. The Urban Forestry Strategic Management Plan, adopted in 2013, was developed to guide the City’s efforts towards a long-term sustainable urban forest.

Kirkland’s Green Building Program encourages new homes to be built to high levels of energy efficiency, conserve and use less water, and use healthier materials in the construction. The program uses Built Green and LEED for Homes as a third party to verify that the home achieves the required certification level. In exchange for the builder or homeowner achieving this certification, the City reviewers agree to expedite the review of the building permit. The City program requires that homes are built tighter than the State Energy Code, exceed requirements for water efficient fixtures, use nontoxic and low emitting materials that are healthier for indoor air quality, and requires that the project reduce waste and recycle left over materials. In addition, testing is done after construction is completed to ensure that the home’s performance meets the certifying program’s standards. However, the scope of the City’s program does not include all building types and therefore the City does not realize quite as many environmental benefits as it could if the program was expanded and included a retrofit component for existing structures.

Kirkland’s Climate Protection Action Plan (CPAP) provides goals for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions which are important because the overall livability of the Kirkland community relies upon the achievement of these goals. While we cannot predict the exact outcome of not achieving them, we do know that taking a cautious and conservative approach is a prudent strategy. An adopted Climate Protection Action Plan that considers government operations and the community’s overall carbon footprint are an excellent starting point. In order to realize the value of this plan, the next steps must be taken to implement the plan and then measure the success of our actions.

What do we need to do to be a more livable and sustainable community?

Questions that should be considered and discussed: Are we doing all we can to restore and regenerate the environment, providing a high quality of life for all residents, promoting the recruitment of businesses that manufacture, retail and operate in a manner that enhances the environment? Do we use and produce renewable energy? Are we reusing our waste so that it becomes a new resource? Are we ensuring that equity exists in Kirkland so that a diverse range of citizens with varying socio-economic backgrounds can actually afford to live in Kirkland, and enjoy the many benefits of a City that is working toward a more livable and sustainable community? The International Living Future Institute, which is located in the Pacific Northwest, is the creator of a stringent building certification (Living Building Challenge) and has developed standards and a robust certification for a Living Communities Challenge (LCC). Kirkland may or may not choose to certify the City as a living community; however, many of the principles from the Living Communities Challenge have been incorporated into the policies of this element.

Here are some of the actions needed to help accomplish this goal:

• Restore our natural systems and critical areas including streams, wetlands, habitat areas and Lake Washington for maximum ecological value and functions.

• Implement the Strategic Urban Forestry Management Plan to enhance our urban forest.

• Revamp Kirkland’s Green Building Program to promote Living Buildings and retrofit existing buildings to be as efficient as possible.

• Develop new codes to provide maximum protection and enhancement of geologic features such as steep slopes, landslide and seismic hazard areas.

• Fund and implement Kirkland’s Climate Protection Action Plan and regional commitments so that we can be readily adaptable and resilient in advance of the effects of climate change.

• Develop a functional Sustainability Master Plan for the City that identifies best practices that allow all of the strategies to be implemented and measured and, if needed, adjusted to achieve a livable and sustainable community.

The policies contained in the Environment Element establish the basis and framework for these concepts and should be utilized to create incentives, regulations, programs and actions to help Kirkland become more livable and sustainable for all current and future generations.

Natural Systems Management

Forbes Creek Wetlands

Natural systems serve many essential biological, hydrological, and geological functions that significantly affect life and property in Kirkland. Features such as wetlands and streams provide habitat for fish and wildlife, flood control, and groundwater recharge, as well as surface and groundwater transport, storage, and filtering. Vegetation, too, is essential to fish and wildlife habitat, and also helps support soil stability, prevents erosion, moderates temperature, produces oxygen, and absorbs significant amounts of water, thereby reducing runoff and flooding. Soils with healthy structure and organic content, such as those found in natural wooded areas, absorb, store, and transport water, effectively supporting vegetation, slope integrity, and reducing flooding and erosion. Clean air is essential to life. In addition to these functions, the natural environment provides many valuable amenities such as scenic landscape, community identity, open space, and opportunities for recreation, culture, and education. Kirkland’s citizens recognize and often comment upon the important role the natural environment plays in the quality of life.

Maintaining these valuable natural systems within Kirkland is a crucial but complex undertaking. Effective management of the natural environment must begin with the understanding that natural features are components of systems which are, in turn, interdependent upon other natural systems that range beyond the City’s borders. The Washington State Growth Management Act and Federal Endangered Species Act underscore this approach and prescribe additional requirements. Accordingly, Kirkland manages the interrelated natural systems:

• Jointly with other agencies and the affected Federally recognized tribes to ensure coordinated and consistent actions among the jurisdictions sharing an ecosystem (e.g., a watershed);

• Comprehensively, by coordinating natural systems information and practices across City departments;

• Scientifically, by applying the best available science to system-wide inventories and analyses to formulate policies and development standards to protect the functions and values of critical areas; and

• Conscientiously, to give special consideration to conservation or protection measures necessary to preserve or enhance anadromous fisheries through salmonid habitat conservation.

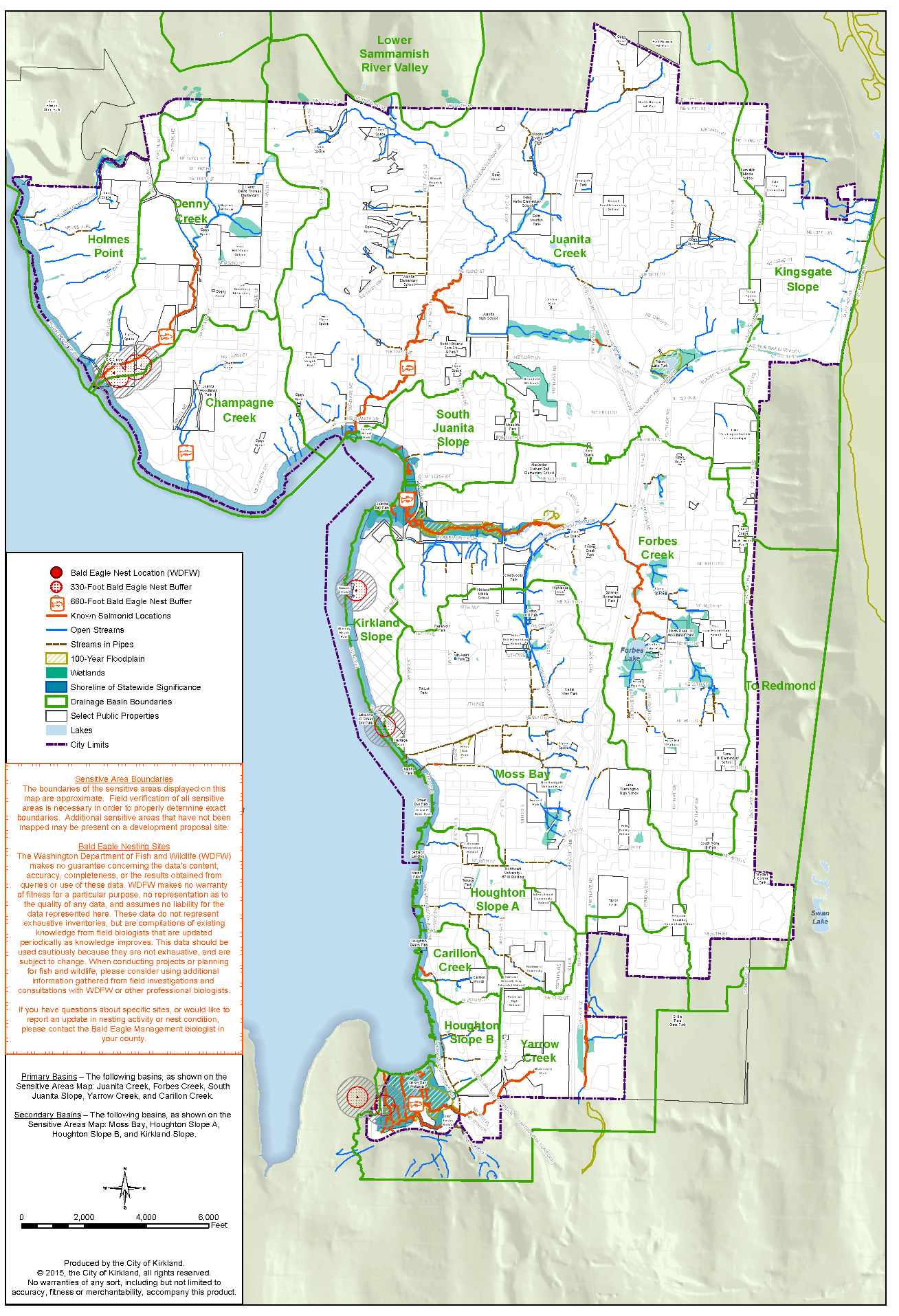

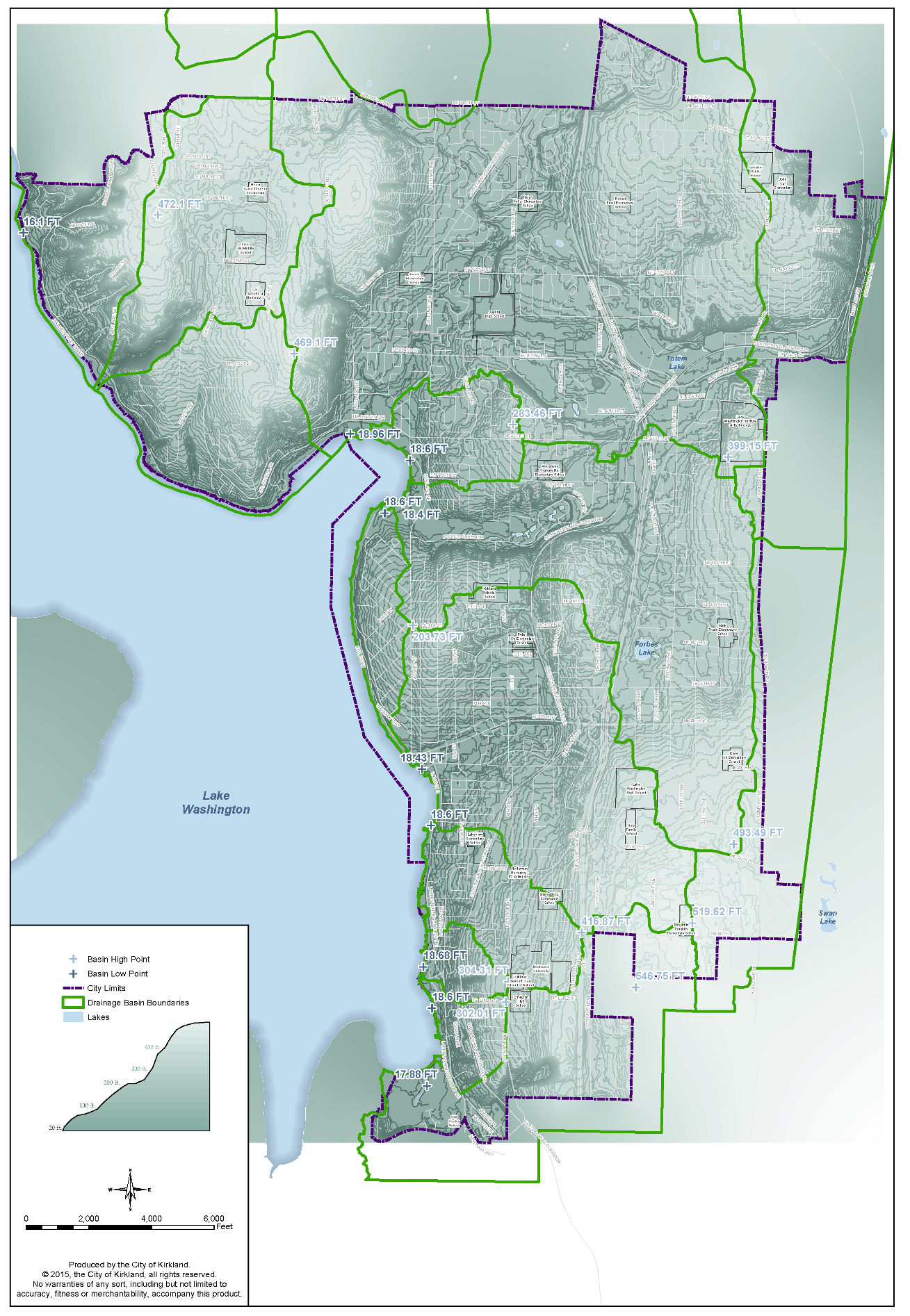

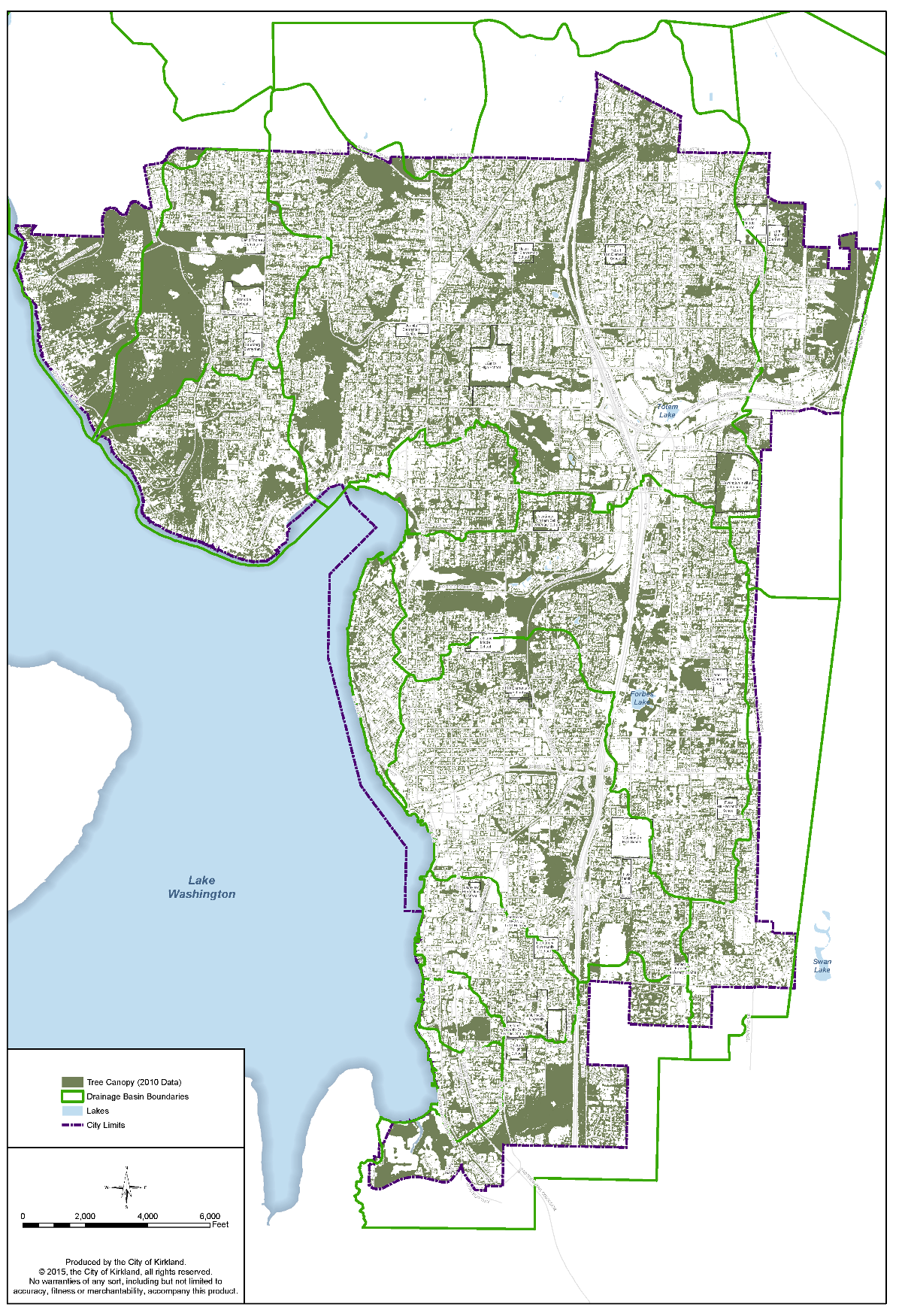

As an urban community with a considerable legacy of environmental resources, Kirkland continues its longstanding effort to balance multiple concerns. The City’s natural resources include 13 drainage basins – some with salmonid-bearing streams, several large wetlands, two minor lakes, and extensive shoreline on Lake Washington (see Figure E-1). Large portions of the City contain steep slopes and mature vegetation (see Figures E-2, E-3, and E-4). Future growth will generally be infill within Kirkland’s well-established, compact land use pattern. Because many of the remaining sites are small and constrained by environmentally sensitive or hazardous areas, Kirkland’s challenge for the future will be to accommodate infill growth and development while protecting and enhancing natural systems on public and private lands.

A variety of tools are needed to effectively manage the natural environment, because natural systems traverse private and public property lines as well as jurisdictional boundaries. These tools include:

• Programs and practices used by the City to maintain land for which it is responsible, such as parks, open space, and rights-of-way;

• Public education and involvement to cultivate a culture of stewardship;

• Incentives to foster sound practices by Kirkland residents, businesses, and institutions;

• Acquisition of the most ecologically valuable sites by the City when feasible; and

• Regulations accompanied by effective enforcement.

The fundamental goal is to protect natural systems and features from the potentially negative impacts of nearby development and to protect life and property from certain environmental hazards. To accomplish this, the Element:

• Recognizes the importance of environmental quality and supports standards to maintain or improve it;

• Supports comprehensive management of activities in sensitive and hazard areas through a variety of methods in order to ensure high environmental quality and to avoid risks or actual damage to life and property;

• Promotes system-wide management of environmental resources. Supports interagency coordination among jurisdictions sharing an ecosystem;

• Supports the acquisition of comprehensive technical data and the application of best available science for natural systems management; and

• Acknowledges the importance of informing the public of the locations, functions, and needs of Kirkland’s natural resources.

Goal E-1: Protect and enhance Kirkland’s natural systems and features.

Policy E-1.1: Use a system-wide approach to effectively manage natural systems in partnership with affected State, regional, and local agencies as well as affected federally recognized tribes.

Environmental resources – such as streams, soils, and trees – are not isolated features, but rather components of ecosystems that go beyond a development site and, indeed, beyond our City boundaries. Therefore, a system-wide approach is necessary for effective management of environmental resources. Also, recognition of the interdependence of one type of natural system upon another is essential. An example of this is the relationship between the shoreline and Lake Washington. For this reason, a comprehensive approach to the management of natural resources is most effective.

Responsibility for management of these ecosystems falls to many agencies at many levels of government, including King County, State resource agencies, and watershed planning bodies. Kirkland and its planning area lie within the Usual and Accustomed Treaty Area of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe. Joint coordination and planning with all affected agencies is appropriate to ensure consistent actions among the jurisdictions sharing an ecosystem.

Policy E-1.2: Manage activities affecting air, vegetation, water, and the land to maintain or improve environmental quality, to preserve fish and wildlife habitat, to prevent degradation or loss of natural features and functions, and to minimize risks to life and property.

The systems and features of the natural environment are considered to be community assets that significantly affect the quality of life in Kirkland. In public rights-of-way, City parks, and on other City-owned land, current technology, knowledge, and industry standards should be proactively used to practice and model sound stewardship practices. For resources on private property, the City should use a combination of public education and involvement, acquisition of prime natural resource areas, and incentives to promote stewardship, as well as regulations combined with effective enforcement.

Because of the many problems caused by adverse impacts to natural vegetation, water, or soils/geologic systems, development should provide site-specific environmental information to identify possible on- and off-site methods for mitigating impacts. The City should be indemnified from damages resulting from development in sensitive or hazard areas, and land surface modification of undeveloped property should be prohibited unless a development application has been approved. Protective measures should also include techniques to ensure perpetual preservation of sensitive areas and their buffers, as well as certain hazard areas.

Policy E-1.3: Manage the natural and built environments to achieve no net loss of the functions and values of each drainage basin; and proactively enhance and restore functions, values, and features.

State and Federal laws require no net loss of functions and values of lakes, streams and wetlands. These laws may also require the protection, enhancement and restoration of these features. Development should avoid or minimize the impacts to these functions and values. Where degradation has occurred, enhancement and restoration should be pursued. Projects, programs and regulations should include mitigation banking when appropriate, adaptive management approaches and Best Available Science standards to preserve and enhance the functions. Limited modification of wetlands and streams that have very low ecological function and value may be allowed, provided these functions and values are fully restored or enhanced.

Policy E-1.4: Pursue restoration and enhancement of the natural environment and require site restoration if land surface modification violates adopted policy or development does not ensue within a reasonable period of time.

The City should look for and act upon opportunities to restore or enhance natural features and systems wherever significant environmental benefits will be realized cost-effectively. Too, land surface modifications that violate the intent of the Goals and Policies should be corrected through site restoration. Developers and property owners should be required to restore the affected sites to a state that approximates the conditions that existed prior to the unwarranted modification. Development should be required to restore the site to a safe condition and re-vegetate areas where vegetation has been removed.

Policy E-1.5: Work toward creating a culture of stewardship by fostering programs that support sound practices, such as low impact development and sustainable building techniques.

Kirkland can promote public environmental awareness and stewardship of sensitive lands in a variety of ways. The City can provide resources and incentives to assist the public in adopting practices that benefit rather than harm natural systems. For example, the City should work with residents, businesses, builders, and the development community to promote low impact development and sustainable building practices. These practices can lower construction and maintenance costs and enhance human health, as well as benefit the environment.

The City should promote and model these practices and others, including purchasing energy efficient and renewable technology products and services whenever feasible, by maintaining model sensitive area buffers, using current arboricultural techniques for public trees, using and eventually certifying new public facilities through programs fostering sustainable building practices, and by linking Kirkland stakeholders to information sources and programs for notable trees, neighborhood planting events, backyard wildlife, and streamside living.

Policy E-1.6: Minimize human impacts on habitat areas and pursue the creation of habitat corridors where wildlife can safely migrate.

Wildlife corridors, also known as habitat corridors, provide a safe passage for wildlife between one area of refuge to another. The Kirkland Streams, Wetlands and Wildlife Study done by the Watershed Company in 1998 identifies some the challenges and opportunities to enhance existing wildlife corridors and should be updated to include mapping of these areas and the most current information about protection, enhancement and restoration and creation of new areas where wildlife can live and thrive. Establishing new or re-establishing these corridors is a mitigation strategy to the effects of urbanization. The City should incentivize the creation of backyard wildlife sanctuaries on private property and encourage larger pieces of property to dedicate permanent conservation easements. For City owned properties, the City should pursue acquisition, enhancement and restoration of land that could be added to Kirkland’s existing wildlife corridors.

Policy E-1.7: Develop a Citywide Sustainability Master Plan.

In 2003, the City adopted the Natural Resource Management Plan to address environmental issues. The City has used the plan to develop new environmental programs, initiatives and regulations. There are many areas, such as operations and development of the City, that could be guided by a comprehensive approach towards sustainability. The City has numerous programs, initiatives and master plans that address certain aspects of sustainability (Surface Water Master Plan, Transportation Master Plan, Urban Forestry Strategic Plan and the Cross Kirkland Corridor Master Plan) but it does not have a functional plan that coordinates all of the City’s efforts using the lens of sustainability.

The City prepares an annual performance measure report that shows how the City is doing based on a set of metrics. A sustainability master plan would develop a set of more refined measurements, such as goals and indicators of success. However, it would also identify strategies and resources necessary to implement the plan. Examples from other cities to consider include the City of Issaquah (Resource Conservation Office), the City of Seattle (Office of Sustainability and the Environment) and the City of Shoreline (Environmental Sustainability Strategy).

Policy E-1.8: Provide information to all stakeholders concerning natural systems and associated programs and regulations.

The City can also increase awareness by allowing access where appropriate to sensitive areas for scientific and recreational use while protecting natural systems from disruption. Careful planning of access trails and the installation of environmental markers and interpretive signs can allow public enjoyment of lakes, streams, or wetlands and increase public awareness of the locations, functions and needs of sensitive areas. In the case of large scale projects on sensitive sites, the City can require developers and property owners to provide additional materials, such as brochures, to inform owners and occupants of the harmful or helpful consequences of their actions in or near sensitive areas and buffers.

Water Systems

Policy E-1.9: Using a watershed-based approach, both locally and regionally, apply best available science in formulating regulations, incentives, and programs to maintain and improve the quality of Kirkland’s water resources.

Juanita Creek Fish Passage

Kirkland’s Streams, Wetlands, and Wildlife Study (July, 1998) is a natural resource inventory of wetlands, streams, fish, wildlife, and habitat areas within Kirkland. A drainage basin or watershed approach was used to identify Kirkland’s drainage systems, to determine primary and secondary basins, and to evaluate and record the primary functions, existing problems and future opportunities for each drainage basin. This data and analysis forms a scientific basis for system-wide resource management that addresses the distinct characteristics of each basin.

Figure E-1 indicates general locations of known sensitive areas and drainage basin boundaries. This study is supplemented by technical information from the Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) 8 salmon conservation planning effort and the City’s Surface Water Master Plan. The WRIA 8 Chinook Salmon Conservation Plan was adopted by the City in 2005 (Resolution R-4510). Since that time Kirkland has provided financial and legislative support and worked collaboratively with other cities within the WRIA 8 watershed to increase funding for salmon recovery and implementation of the plan.

Policy E-1.10: Prioritize removing fish passage barriers for public projects.

Culverts and other structures may pose physical barriers to fish, resulting in loss of habitat and population decline. The removal of fish passage barriers for the City’s public projects is not a requirement, but the State has created a board to develop an inventory of existing barriers under City and county roads and a prioritized removal list.

Consequently, the City’s Surface Water Master Plan (SWMP) has developed an inventory of publicly owned culverts and their fish passage barrier status. The SWMP has also prioritized those barriers for removal, and developed conceptual designs and cost estimates for removal of the first few barriers. This inventory needs to be kept up-to-date, and should be augmented with an inventory of fish passage barriers that exist on private property.

Policy E-1.11: Support removal of fish passable barriers and daylighting of streams on private property.

For many years it was believed that conventional piped drainage systems were the best method for handling all drainage in urban areas. Consequently, as rights-of-way and properties developed, segments of Kirkland’s streams were placed in pipes. Over time it has been observed that open drainage can be more effective than conventional detention and engineered conveyance. The size, shape and placement of the pipes can also cause a barrier that prohibits fish migration upstream. In addition, piped drainage systems can cause increased flooding, decreased water quality, decreased ground water recharge, loss of fish and wildlife habitat, loss of urban forest, and reduced viability of streams and wetlands due to lost natural hydrological systems.

One way to restore these connections and promote fish passable barriers is to remove the stream segments in pipes and daylight them in natural channels. While there may be challenges to doing this such as financial costs and loss of property due to providing a buffer and day lit channel, the benefits may outweigh these costs and challenges. The City should prioritize private piped stream segments for daylighting and removal of fish passable barriers and encourage this change by pursuing grant funding, creating incentive programs, removal of disincentives, and adopting updated regulations.

Policy E-1.12: Protect surface water functions by preserving and enhancing natural drainage systems.

The City should look for and act upon opportunities to restore or enhance natural features and systems wherever significant environmental benefits will be realized cost-effectively. Too, land surface modifications that violate the intent of the goals, policies and regulations should be corrected through site restoration. Affected sites should be restored to a state which approximates the conditions that existed prior to the unwarranted modification. Development should be required to restore the site to a safe condition and re-vegetate areas where vegetation has been removed.

Policy E-1.13: Comprehensively manage activities that may adversely impact surface and ground water quality or quantity.

Increases in impervious surface resulting from development result in decreases in ground water recharge. This, in turn, results in a decline in base flows and subsequent loss of habitat that impacts fish and wildlife populations.

Urban runoff often contains pollutants such as gasoline, oil, sediment, heavy metals, herbicides, and other contaminants. These materials degrade the quality of water in our streams and lakes. Steps to limit contamination include:

• Prohibit the dumping of refuse or pollutants in or next to any open watercourse, wetlands or into the storm drainage system. Dumped refuse and pollutants can contaminate surface and subsurface water and can physically block stream flows;

• Provide education to businesses and residents about the role that each plays in maintaining and improving water quality;

• Require projects to provide water quality treatment facilities if they propose to alter or increase significant quantities of impervious surface that generate pollution; and

• Preserve and enhance sensitive area buffers to maximize natural filtration of contaminants. Pursue opportunities to improve buffer viability by improving maintenance of buffer vegetation.

Policy E-1.14: Respond to spills and dumping of materials that are impactful to the environment.

The City should take a proactive approach and provide funding for immediate response to spills and dumping of hazardous materials and pollutants within the City. It is far easier and cost effective to prevent damage rather than mitigate degradation of Kirkland’s streams, wetlands and lakes. Spill control and cleanup is required per the City’s Phase II NPDES Municipal Stormwater Permit. It is far easier to clean up spills and prevent pollutants from reaching our waterways, than to try and clean polluted lakes and streams.

Surface Water

The City adopted an updated Surface Water Master Plan in 2014. This plan outlines the priorities and needs for surface water management and related programs, requirements and activities in the City. Implementation of the plan is important for the City in its overall efforts to address stormwater runoff, water quality, flooding and environmental protection.

Policy E-1.15: Improve management of stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces by employing low impact development practices through City projects, incentive programs, and development standards.

As land is developed, the loss of vegetation, the compaction of soils, and the transformation of land to impervious surface all combine to cause uncontrolled stormwater runoff to degrade streams, wetlands and associated habitat; to increase flooding, and to make many properties wetter. Low impact development practices minimize impervious surfaces, and use vegetated and/or pervious areas to treat and infiltrate stormwater. Such practices can include incentives or standards for landscaped rain gardens, permeable pavement, narrower roads, vegetated rooftops, rain barrels, impervious surface restrictions, downspout disconnection programs, “green” buildings, street edge alternatives and soil management.

Policy E-1.16: Retrofit existing impervious surfaces for water quality treatment and look for opportunities to provide regional facilities.

New development has limitations on impervious surfaces and requires water quality treatment of stormwater based on adopted stormwater design regulations.

While it is important to regulate new development, the bulk of change in Kirkland’s stormwater infrastructure will occur through redevelopment. Partnering with private properties may be a cost-efficient way to achieve regional water quality treatment, as it is usually far less expensive to build facilities in parking lots rather than beneath public right-of-way which is encumbered by numerous utilities. The City should pursue grant funding, incentive programs, regulations and planning for retrofitting existing impervious areas to improve water quality treatment and further the goals of the Surface Water Master Plan.

Flood Storage

Policy E-1.17: Preserve the natural flood storage function of 100-year floodplains and emphasize nonstructural methods in planning for flood prevention and damage reduction.

Floodplains are lands adjacent to lakes, rivers, and streams that are subject to periodic flooding. Floodplains naturally store flood water, protect water quality, and provide recreation and wildlife habitat. New development or land modification in 100-year floodplains should be designed to maintain natural flood storage functions and minimize hazards to life and property (see Figure E-1).

Policy E-1.18: Make allowances for connections between existing streams and their floodplain to increase floodplain storage.

Funding, construction and maintenance of vaults or tanks upstream can be more costly and difficult than finding in-channel areas to store water to increase floodplain storage. The City should identify and implement floodplain storage near existing streams to reduce water velocities that benefit fish and other aquatic organisms and can translate into less flooding and property damage.

TREES AND VEGETATION

Trees and vegetation – primary elements of the urban forest – enhance Kirkland’s quality of life, minimize the effects of urbanization, and contribute to and define community character. Unfortunately, many urban elements negatively impact trees, shortening their normal life expectancy and risking overall canopy loss. It is important that municipal planning and management efforts direct the urban landscape to maximize the public benefits that trees and vegetation provide over a long-term horizon.

Goal E-2: Protect, enhance and restore trees and vegetation in the natural and built environment.

Policy E-2.1: Strive to achieve a healthy, resilient urban forest with an overall 40 percent tree canopy coverage.

Healthy trees and vegetation provide numerous ecological benefits, including filtration and interception of stormwater runoff, improved air quality, reduced atmospheric carbon, erosion reduction, hillside and stream bank stabilization, and temperature moderation; thereby reducing the urban heat island effect, and provision of fish, wildlife and pollinator habitat. In addition, trees provide numerous economic, social and aesthetic benefits.

Significant improvements in stormwater management and air quality could be realized if the tree canopy cover of 40 percent was maintained1. A sustainable urban forest consists of diverse tree ages and species, both in native and planted settings. Larger, mature trees should be maintained and protected, as the greatest benefits accrue from the continued growth and longevity of larger trees.

Policy E-2.2: Implement the Urban Forestry Strategic Management Plan.

To ensure that trees function well in their intended landscape and provide optimal benefits to the community over a long-term horizon, urban forests require sound and deliberate management. In order to track progress, it will be important to complete, then monitor and maintain, a public tree inventory, assess the environmental benefits of Kirkland’s urban forest, as well as to assess the urban tree canopy cover at least every 10 years. The City’s Urban Forestry Strategic Management Plan should be updated and revised every six years to reflect current knowledge, technology, and industry standards.

Policy E-2.3: Provide a regulatory framework to protect, maintain and enhance Kirkland’s urban forest, including required landscaping standards for the built environment.

Where development may occur, care should be taken to plan for and use site specific development practices and regulations to minimize removal or destruction of trees, particularly significant stands of native evergreen trees, natural woodlands and associated vegetation and sensitive area buffers.

In the built and paved environment, trees, shrubs and groundcovers function to screen adjacent land uses and activities, define views, and unify and organize disparate site elements. Plantings can reflect the character of and transition to adjacent areas, and attract customers to businesses by increasing visual appeal. Foliage can reduce reflection or glare from street lights or vehicles, making an area more hospitable and safe; while dense foliage can absorb and disperse sound. Energy cost savings can be realized by arranging plants around buildings for an insulating effect from extreme temperatures and to deflect wind.

Policy E-2.4: Balance the regulatory approach with the use of incentives, City practices and programs, and public education and outreach.

Incentives can promote stewardship of natural resources on private land by rewarding sound practices. Examples may include saving time and money in the permitting process, allowing variations to development codes, discounting utility rates, offering vouchers for plant materials, providing technical assistance/cost sharing for restoration or enhancement of natural areas, and public recognition for developers or sites that exemplify excellence or innovation in tree retention.

Examples of increasing awareness and educating the community about the goals and challenges of managing the urban forest may include providing materials, workshops and presentations for developers, arborists, and homeowners. A greater emphasis on community outreach can help generate the support and community vision necessary for a healthy, sustainable urban forest.

Policy E-2.5: Collaborate with overlapping jurisdictions to align Kirkland’s tree protection with the needs of utility providers, transportation agencies and others to maximize tree retention and reduce conflicts with major projects.

Urban trees are regarded more and more as assets similar to other infrastructure investments. When major projects in Kirkland are planned, combined efforts and mutual cooperation and support produce efficiencies and cost savings, preventing tree preservation conflicts that may arise with overlapping jurisdictions such as in the I-405, Sound Transit, Seattle City Light, and Puget Sound Energy corridors. Consultation by these jurisdictions with the City should occur to ensure that trees and vegetation are only removed when necessary and that appropriate replanting occur consistent with City policies and standards. Vegetation management plans, particularly for utility corridors, should be established to guide removal and pruning operations and activities.

SOILS AND GEOLOGY

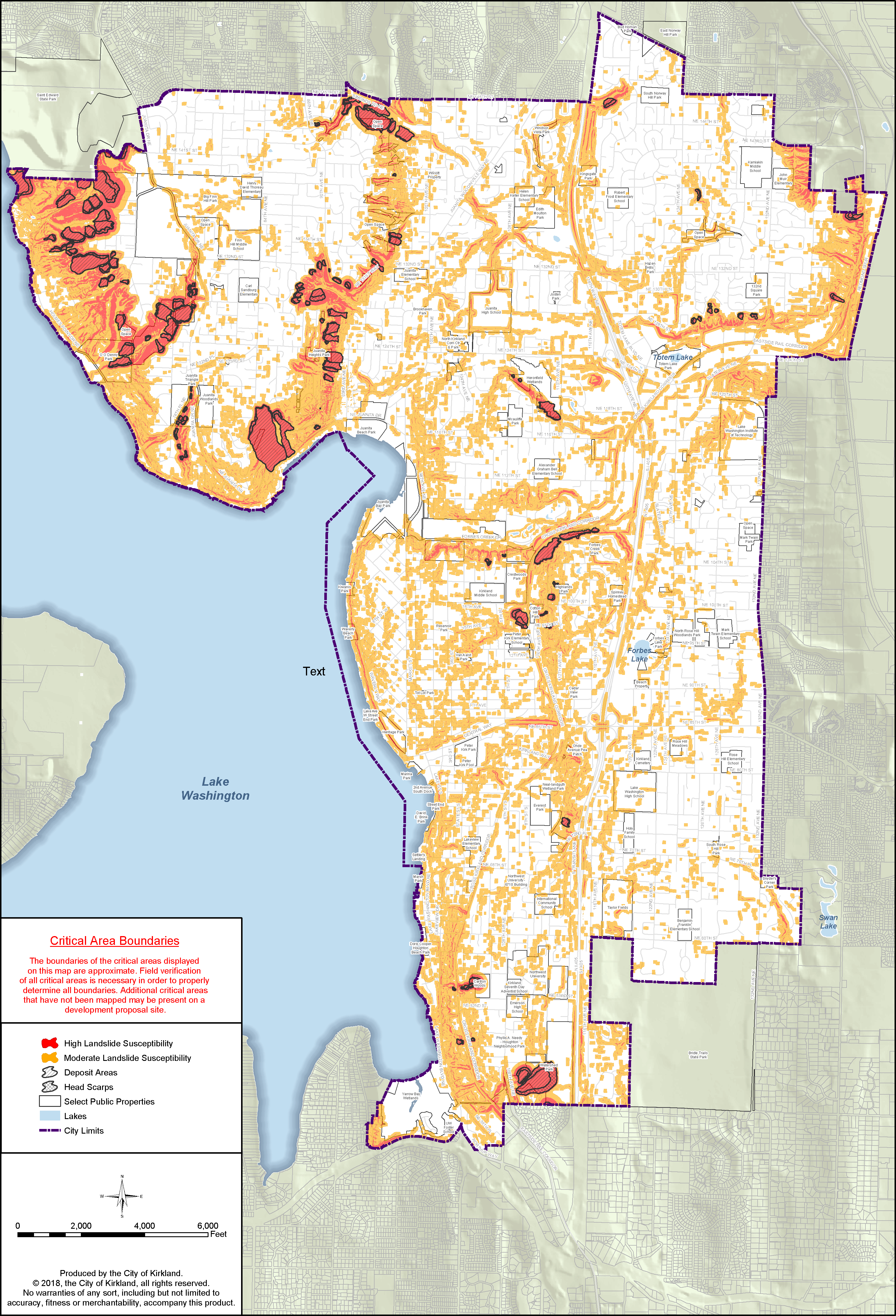

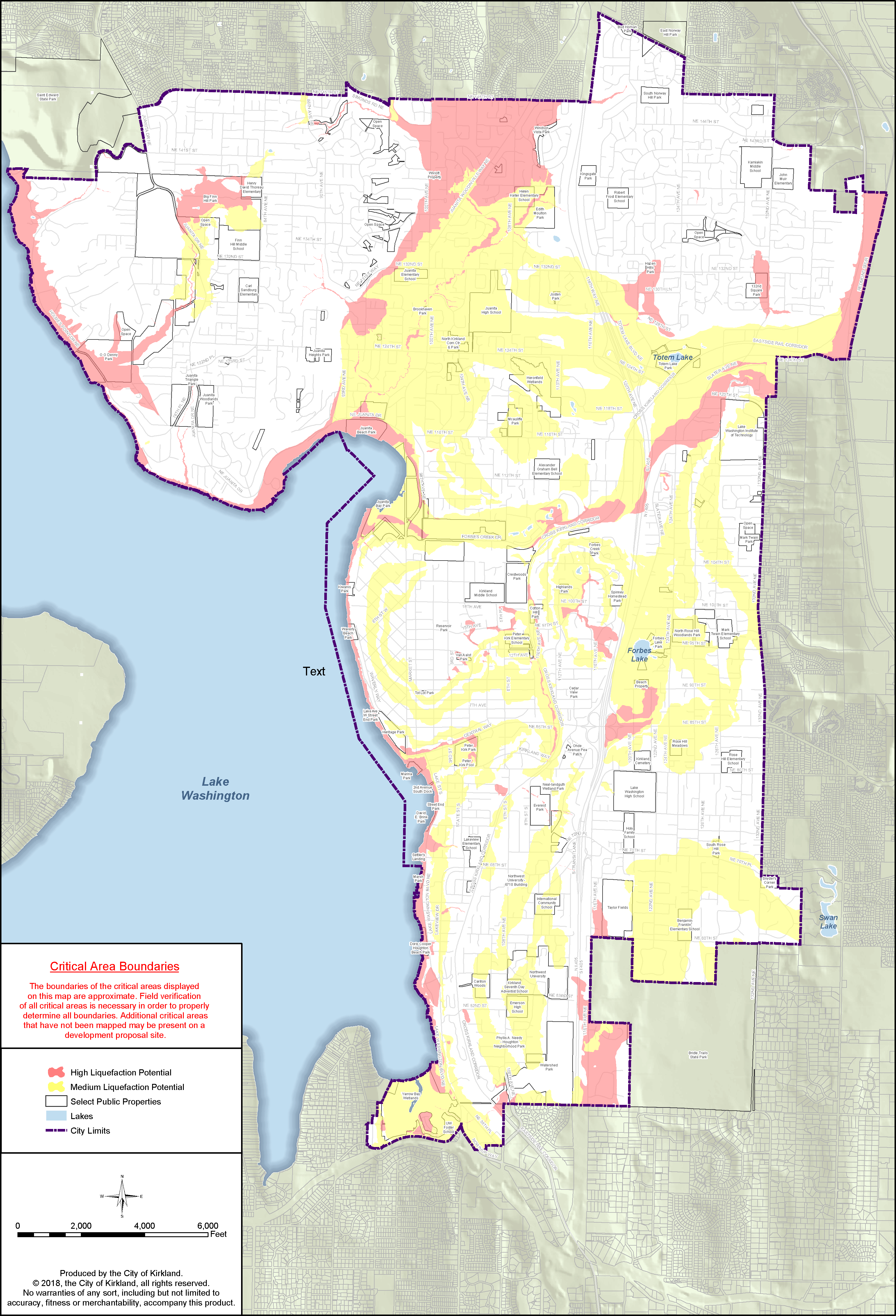

Geologically hazardous areas are defined as critical areas under the Growth Management Act. These consist of landslide, erosion and seismic hazard areas. They pose a potential threat to the health and safety of the community. Many areas of the City have steep slopes and ravines subject to erosion and hazardous conditions (earthquakes and landslides). Geologically hazardous areas are mapped depicting the general location and presence of these areas based on available geologic and soils information. (See Figure E-2, Geologically Hazardous Areas).

Landslides are highly probable in many steep and unstable slope areas, regardless of development activity. Landslides may be triggered by grading operations, land clearing, irrigation, or the load characteristics of buildings on hillsides. Damage resulting from landslides may include loss of life and property, disruptions to utility systems, or blockage of transportation and emergency access corridors. For these reasons, development is regulated where landslides are a potential hazard. In some cases, regulation may result in severe limitations to the scale and placement of development, and land surface modification should be limited to the smallest modification necessary for reasonable site development.

In the Puget Sound area, possible damage to structures on some unstable slopes or wetland areas can be caused by low-intensity tremors. This is especially true when hillsides composed of clay and/or organic materials are saturated with water. Slopes with grades of 15 percent or steeper are also subject to seismic hazards. Areas with slopes between 15 and 40 percent or greater are particularly vulnerable. Low-intensity earth tremors could cause liquefaction and damage development in wetland areas composed of organic or alluvial materials. In hillside and wetland areas, structures and supporting facilities need to be regulated and designed to minimize hazards associated with earthquakes. The City should provide information to the public about potential geologic hazards, including site development, building techniques and disaster preparedness.

Goal E-3: Improve public safety by avoiding or minimizing impacts to life and property from geologically hazardous areas.

Policy E-3.1: Require appropriate geotechnical analysis, sound engineering principles and best management practices for development in or adjacent to geologically hazardous areas.

The City’s Landslide and Hazard Areas Map shows the general location of these areas. The determination of the actual conditions and characteristics of these hazards on or near property is based on detailed scientific and geotechnical engineering analysis and principles. The City can require geotechnical investigations, reports and recommendations by a qualified engineer when development is proposed or restoration activities are being considered in or adjacent to geologically hazardous areas. The City should continue to identify landslide areas and provide this information to the public.

Policy E-3.2: Regulate land use and development to protect geologic, vegetation and hydrological functions and minimize impacts to natural features and systems.

Geologically hazardous areas, especially steep forested slopes and hillsides, provide multiple critical area functions. Performance standards, mitigating conditions, or limitations and restrictions on development activity may be required. Clustering of development away from these areas should be encouraged or required. Using natural drainage systems, retention of existing vegetation and limitations on clearing and grading are preferred approaches.

Policy E-3.3: Utilize best available science and data for seismic and landslide area mapping.

Governor Jay Inslee convened an SR 530 Landslide Commission to identify lessons learned from this catastrophic event. The Commission released its report in December, 2015 and noted the following:

The SR 530 Landslide highlights the need to incorporate landslide hazard, risk, and vulnerability assessments into land-use planning, and to expand and refine geologic and geohazard mapping throughout the State. The lack of current, high-quality data seriously hampers efforts under the Growth Management Act (RCW 36.70A) and other regulatory programs to account and plan for these hazards. Use LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) mapping to target high priority areas hazardous to people or property. Ensure that landslide hazard and risk mapping occur in the highest priority areas first, including transportation corridors, such as the Everett-Seattle rail line and the trans-Cascades highways, residential areas, urban growth areas, emergency evacuation routes, and forest lands…

The City has relied on geologic and soils mapping done by King County in the early 1990s. In 2011 the City undertook a comprehensive geologic detailed mapping of the pre-annexation portion of the City. The City should complete the surficial and soils mapping for the entire City and conduct a hazard and risk assessment utilizing best available science. Kirkland’s programs, practices and regulations relating to geologic hazard areas, clearing and grading, vegetation, and critical areas should be evaluated once the assessment has been completed. As new information or better science evolves or as conditions change, policies, regulations and programs should be regularly updated.

Policy E-3.4: Retain vegetation where needed to stabilize slopes.

Significant vegetation as cover on hazard slopes can be important, because plants intercept precipitation reducing peak flow, runoff, and erosion that can impact water quality and slope stabilization. Vegetated ravines also provide habitat linkages for wildlife. Avoiding disturbance of steep slopes and their vegetative cover should be a high priority. Natural Growth Protection Easements should be required where needed to protect these areas.

Policy E-3.5: Promote sound soil management practices through standards, regulations and programs to limit erosion and sedimentation.

Healthy soil provides nutrients to support vegetation and habitat for subsurface organisms, and it absorbs, cleans, stores, and conveys water, thereby improving water quality and moderating water quantity. Mismanagement or neglect of soil can result in increased flooding, loss of vegetation, sedimentation of watercourses, erosion, and landslides – all of which degrade habitat for humans as well as for other species. Soil erosion should be controlled during and after development through the use of best available technology and management practices. The City should have both standards to address soil erosion and programs so that valuable topsoil will be conserved and reused and soil for required plantings will be amended as appropriate.

BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Ensuring that sustainable development principles such as those used in the International Living Future Institute’s Living Building Challenge (LBC) are used when land is developed or redeveloped in Kirkland is an effective strategy for managing the built environment in order to create a livable community that can exist in harmony with natural systems. The Living Building Challenge™ is the built environment’s most rigorous performance standard. It calls for the creation of building projects at all scales that operate as cleanly, beautifully and efficiently as nature’s architecture. To be certified under the Challenge, projects must meet a series of ambitious performance requirements over a minimum of 12 months of continuous occupancy. Some of the areas that are measured fall under headings such as Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity and Beauty. If all of the performance standards are achieved, the building helps regenerate the environment by producing all of its own energy, harvesting its own water, processing all of its waste and offsetting impacts of its construction. There are only a handful of certified Living Buildings world-wide, but this is changing and soon there will be more buildings that give more back to the environment than they take from it.

Achieving any of the LBC principles can be challenging. Technology is changing daily, and building, stormwater and energy codes are lagging behind. Current codes can be improved to address healthier building materials. These same codes could be modified so that buildings harvest the energy or the water that it uses. However, it is possible today for structures in the built environment to be designed and constructed to create a net-positive effect. Even existing structures can be retrofitted to be more efficient and reduce the impacts on the environment.

The City has a prime opportunity to provide leadership in the built environment by constructing its own facilities to the highest sustainability standards or applying some of the best practices from the Living Building Challenge. The City can also promote and encourage sustainable development by supporting the incorporation of Living Building Challenge principles in the State building, energy and stormwater codes. Working in collaboration with other regional partners to ramp up these requirements will spur more technological advances in the building industry, which in turn will help get more living buildings in Kirkland and ensure that the community is livable now and for future generations.

Goal E-4: Manage the built environment to reduce waste, prevent pollution, conserve resources and increase energy efficiency.

Policy E-4.1: Expand City programs that promote sustainable building certifications and require them when appropriate.

The City developed an expedited green building program for single-family homes in 2009. Applications that qualify can get priority review of the permit. Many builders and homeowners have taken advantage of reduced permit review times in exchange for building sustainable structures that help the City further reduce energy and resource use. These types of programs are also important because they promote healthy indoor air quality and reduce greenhouse gas emissions which support other City policies. The existing program should be updated to consider other incentives and to include all structures such as commercial and mixed use buildings and major renovations of existing structures so that all building types can be built more sustainably.

Larger developments, and projects that require a master plan should be required to achieve a sustainability certification, utilizing certification programs such as LEED or Built Green. The level of certification should be evaluated by the type and size of the development.

Policy E-4.2: Design, build and certify public building projects to LEED, Living Building Challenge or equivalent certification standards.

The City currently builds its public facilities to meet at least a LEED “Silver” certification. There are other certifications such as the International Living Future Institute’s Living Building Challenge that move beyond merely reducing environmental impacts by restoring and regenerating the natural environment through the construction of “living buildings.” Living buildings harvest and clean their own water, clean their wastewater and produce and use their own clean renewable energy. The City should consider moving to a LEED Gold certification level as a goal and begin utilizing portions of the Living Building Challenge certification with the intent of eventually constructing “living buildings.”

Policy E-4.3: Implement energy efficiency projects for City facilities, and measure building performance through Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Energy Star or equivalent program.

The City strives to increase the energy efficiency of its buildings and infrastructure such as street lights and signals and has measured the effectiveness of building improvements by using the EPA’s portfolio manager program. The City should continue to look for ways to further reduce energy use and support local and regional climate change emission reduction targets by supporting local solar campaigns, using Photovoltaic Solar Panels (PV) on City facilities to generate clean renewable energy and purchasing electric and clean energy vehicles for the City’s fleet.

Swale at Kirkland Justice Center

Policy E-4.4: Utilize rigorous sustainability standards and green infrastructure in all City projects.

There are many programs that exist to measure the sustainability of buildings, but there are very few that measure and certify the other types of projects such as roads, sewer and stormwater projects as identified in the City’s Capital Improvement Program (CIP). As part of the project’s design, the City should incorporate environmental or sustainability measures.

This could be done by considering more than just the initial costs to design and build infrastructure projects. The cost of an infrastructure project could look at installing purple stormwater pipe and reclaiming that water for other uses. Prioritization should be placed on reducing the environmental impacts of these infrastructure projects throughout the entire project development process from conception to completion and maintenance. This could include hiring consultants and contractors that are specialists in the design and construction of greener, more sustainable infrastructure. The City should certify these types of projects by using the King County Sustainability Scorecard if there are not any recognized sustainability certifications available.

Policy E-4.5: Utilize life cycle cost analysis for public projects that benefit the built and natural environment.

Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) is a concept that considers the total cost of ownership for improvements such as City buildings and infrastructure over its lifetime. There are many factors to consider when proposing a project, and budget has traditionally been very important. Criteria that allows the total costs, both financial and environmental, should be considered, prior to commencing a Capital Improvement Project. The positive benefits of employing an environmental lens can help reduce facility operations and maintenance costs, reduce use of resources such as water and energy and further the City’s goals to enhance the natural and built environment.

Policy E-4.6: Work with regional partners such as Regional Code Collaborative (RCC) to build on the Washington State Energy Code, leading the way to “net-zero carbon” buildings through innovation in local codes, ordinances, and related partnerships.

One technique to increase energy efficiency is to make the energy code more stringent and thereby codifying highly efficient structures. This can be done by working with regional partners as Kirkland does not have its own energy code and uses the Washington State Energy Code. Another strategy could be to incentivize owners of existing structures to upgrade their buildings and reduce energy usage by working with utility providers to help incentivize these improvements. Both new and existing building owners will need appropriate tools to do this. Another technique is to work with other cities and building associations such as the King and Snohomish County Master Builders to build a workforce to implement a regional energy efficiency retrofit economy. In order for these efforts to be successful they must have participation from owners of existing and new buildings.

Water storage tanks, Kirkland Justice Center

Policy E-4.7: Work with regional partners to pursue 100 percent use of a combination of reclaimed, harvested, grey and black water for the community’s needs.

A livable and sustainable community plans ahead and works towards ensuring that a vital resource such as water continues to be available for future generations. A prudent and conservative approach would include reusing and capturing water to be used for other purposes instead of letting it become storm or wastewater after one use. Rainwater can be harvested for watering plants such as food gardens. Grey water that has been used for washing dishes could be captured and used to water non-edible landscaping. Black water, which is sewage, can be processed on a site or community scale and could create compostable resources such as natural fertilizer for plants while simultaneously putting minerals back into the soil. These and other measures take pressure off of the use of clean, potable drinking water for nonpotable uses and thereby preserving valuable water.

Policy E-4.8: Work with regional partners to achieve 70 percent recycling rate by 2020 and net zero waste by 2030.

Kirkland Solid Waste has been tremendously successful in the achievement of some of the highest recycling rates in King County. Working with regional partners such as Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Advisory Committee, Kirkland can do more to increase these rates in areas such as multifamily and commercial establishments. In addition, continuing to work to educate citizens, businesses and manufacturers about waste reduction can help in achieving these goals and reduce the need for landfills.

Policy E-4.9: Promote public health and improve the natural and built environments by prohibiting the release of toxins into the air, water and soil.

A livable community does not permit placing toxins into the environment and this includes allowing materials with known harmful effects to humans to be used in the construction of new and existing structures. The International Living Future Institute’s Material Red List can be used for guidance. It may not be possible to source materials that don’t include toxic chemicals, but being aware of them and not using them in City projects and discouraging their use in private projects could result in the market producing healthier materials for construction.

Policy E-4.10: Promote preservation and adaptive reuse of existing structures.

The City has a history of reusing existing buildings such as the Kirkland Annex which was an old single-family home that became City offices. The City also repurposed a former Costco Home structure into a Public Safety Building. This preservation strategy has environmental, financial and historical/cultural implications.

First, it recognizes the embodied energy and the monetary value of the materials in existing buildings. If these materials from an existing building are destroyed it creates waste and pollution. Second, it conserves the natural raw materials that would be needed to create new construction materials. In addition, there are financial costs that are avoided by reusing, salvaging, and repurposing existing structures or materials. Last, in the case of the Kirkland Annex, restoring a historical structure and preserving a piece of Kirkland’s history is an important facet of keeping the community character intact for future generations to enjoy. The City should continue to look for these kinds of opportunities and develop incentive programs and initiatives to encourage private owners to preserve and reuse structures throughout the City.

Policy E-4.11: Promote and recognize green businesses in Kirkland.

This City should build upon its existing Green Business program and develop a robust program that is used by all businesses in Kirkland. Although this program would be voluntary, it could be a tool for business to help market themselves as a sustainable, green business to consumers. The use of the International Living Future Institute’s (ILFI) JUST label could be a way to show consumers how the business enhances the local economy, a better environment and promotes social equity. Additionally, ILFI’s DECLARE label could be utilized to show consumers the ingredients in the items they purchase from green business program members.

Policy E-4.12: Promote and encourage Citywide sustainable product stewardship to provide stable financing for end-of-life management of consumer products, increase recycling and resource recovery, and reduce environmental and health impacts.

Product Stewardship is an environmental management strategy that means whoever designs, produces, sells, or uses a product takes responsibility for minimizing the product’s environmental impact throughout all stages of the product’s life cycle. The greatest responsibility lies with whoever has the most ability to affect the life cycle environmental impacts of the products.

The City (Solid Waste) is a Full Member of the Product Stewardship Institute and an Associate Member of the NW Product Stewardship Council (NWPSC). The City should consider participating on the NWPSC Steering Committee. The City is a large purchaser of goods and services and should provide leadership by incorporating the principles of product stewardship into its own purchasing policies as a means to influence businesses and consumers in the community to do the same.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change, also referred to as global warming, refers to the rise in average surface temperatures on Earth. An overwhelming scientific consensus maintains that climate change is due primarily to the human use of fossil fuels, which releases carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the air. The gases trap heat within the atmosphere, which can have a range of effects on ecosystems, including rising sea levels, severe weather events, and droughts that render landscapes more susceptible to wildfires.

Kirkland can take an active role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). Climate change has the potential to impact public and private property, infrastructure investments, water quality, and health. The consequences can be significant from warming temperatures, rising seas, decreasing snowpack, and increased flooding.

A carbon footprint is the measure given to the amount of greenhouse gases produced by burning fossil fuels, measured in units of carbon dioxide. Carbon neutrality means that both City operations and the community balance the carbon released into the air with an equal amount of clean renewable energy production. There are many possible ways to achieve this goal. A best management practice is to first reduce the amount of carbon produced, so that the netting out at zero becomes more feasible. A complementary strategy would be to offset the carbon dioxide released from using fossil fuels with the production and use of renewable energy such as solar and wind.

For government operations this would include implementing energy efficiency improvements within City facilities and infrastructure and also producing and using renewable energy sources. For the broader Kirkland community this means creating more energy efficient structures and working directly with local utility providers to provide more renewable energy options. This will take a significant effort by all to achieve, but it is important to realize that it is possible with a comprehensive approach that includes a focus on transportation, land use, solid waste, urban forestry, local and state building codes, advocacy and regional collaboration.

Kirkland’s Climate Change Efforts

For over 15 years Kirkland has engaged in work related to addressing the impacts of climate change. These efforts include:

In 2000, an interdepartmental team, since named the Green Team, was formed to coordinate all of the City’s actions for managing Kirkland’s natural and built environment.

In 2003, the City Council adopted the Kirkland Natural Resource Management Plan, by Resolution R-4396, which comprehensively summarizes best resource management practices and principles, Kirkland’s natural resource management objectives, and recommended implementation strategies.

In 2005, Kirkland endorsed the U.S. Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement, committing to help reverse global warming by reducing greenhouse emissions.

In 2006, Council authorized Kirkland’s membership in the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) by Resolution R-4591, which allowed the City to participate in the Cities for Climate Protection 5 milestones campaign. The milestones are:

1. Conduct a greenhouse gas inventory.

2. Establish greenhouse gas reduction target.

3. Develop an action plan to meet the GHG target.

4. Implement the action plan.

5. Monitor and report progress.

In 2007, Council adopted greenhouse gas reduction targets via Resolution R-4659 for both the community as well as government operations. The reduction targets were:

• Interim: 10 percent below 2005 levels by 2012

• Primary: 20 percent below 2005 levels by 2020

• Long-term: 80 percent below 2005 levels by 2050

In 2009, Council adopted the Climate Protection Action Plan by Resolution R-4760 to achieve the greenhouse gas reduction targets. To determine Kirkland’s progress in meeting its government operations and community reduction targets, the City committed to the following:

• Monitor progress on each of the efforts and measures the City outlined in the Plan at least annually so that, as needed, program revisions and corrections are timely.

• Update the greenhouse gas inventory for government operations annually.

• Update the greenhouse gas inventory every three years for the community.

• Compare the updated inventory with that of the base year’s and determine how close the City is to the target reductions.

• Provide an annual Climate Protection Action Report to the City Council and the community.

In 2012, Kirkland helped found the King County Climate Change Collaborative (K4C) along with King County and other King County cities and signed an interlocal agreement to work in partnership with the K4C on local and regional climate change efforts.

In October 2014, the council authorized the Mayor to sign Resolution (R-5077), Joint Letter of Commitments: Climate Change Actions in King County, which supports the Joint County – City Climate Commitments of the K4C Cities and aligns Kirkland’s greenhouse gas emission reductions with that of King County and signatory cities. The new reduction targets use 2007 as the baseline year, retain the 2050 reduction target and add a midpoint goal in 2030 to bridge the gap between 2020 and 2050.

Goal E-5: Target carbon neutrality by 2050 to greatly reduce the impacts of climate change.

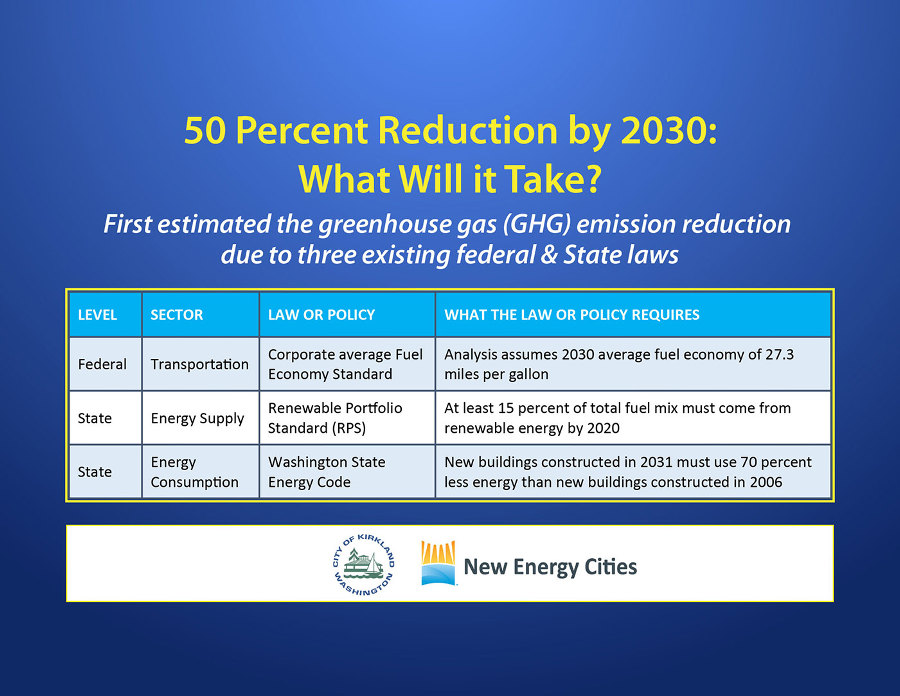

Policy E-5.1: Achieve the City’s greenhouse gas emission reductions as compared to a 2007 baseline:

• 25 percent by 2020

• 50 percent by 2030

• 80 percent by 2050

Resolution R-5077 revises Kirkland’s existing emission reduction baseline year from 2005 to 2007 and aligns the emission reduction percentages and milestone years (2020, 2030 and 2050) to be consistent with the King County Climate Change Collaborative (K4C).

The City has adopted these greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions to be consistent with the new Countywide targets and has committed to working with the K4C on regional solutions in areas such as transportation, renewable energy production and fuel standards. It will be important to also develop and adopt near- and long-term government operational GHG reduction targets that support Countywide goals.

Policy E-5.2: Regularly update the City’s Climate Protection Action Plan (CPAP) in order to respond to changing conditions.

Kirkland’s CPAP should be revised due to the emission reduction changes required as part of signing the K4C Joint Commitments Letter. In addition, implementation strategies to achieve the CPAP should be monitored, evaluated and revised as necessary on an annual basis.

Policy E-5.3: Fund and implement the strategies in Kirkland’s Climate Protection Action Plan (CPAP).

Kirkland’s government operations met its previous 2012 emission reduction targets as defined in the CPAP due to energy efficiency measures and by purchasing renewable “green” power from Puget Sound Energy. Strategies for the community emissions are being developed in 2015. These reductions are a much bigger challenge because they include all sources of GHG emissions of which Kirkland does not have direct control, such as transportation, private business operations and the consumption patterns of citizens.

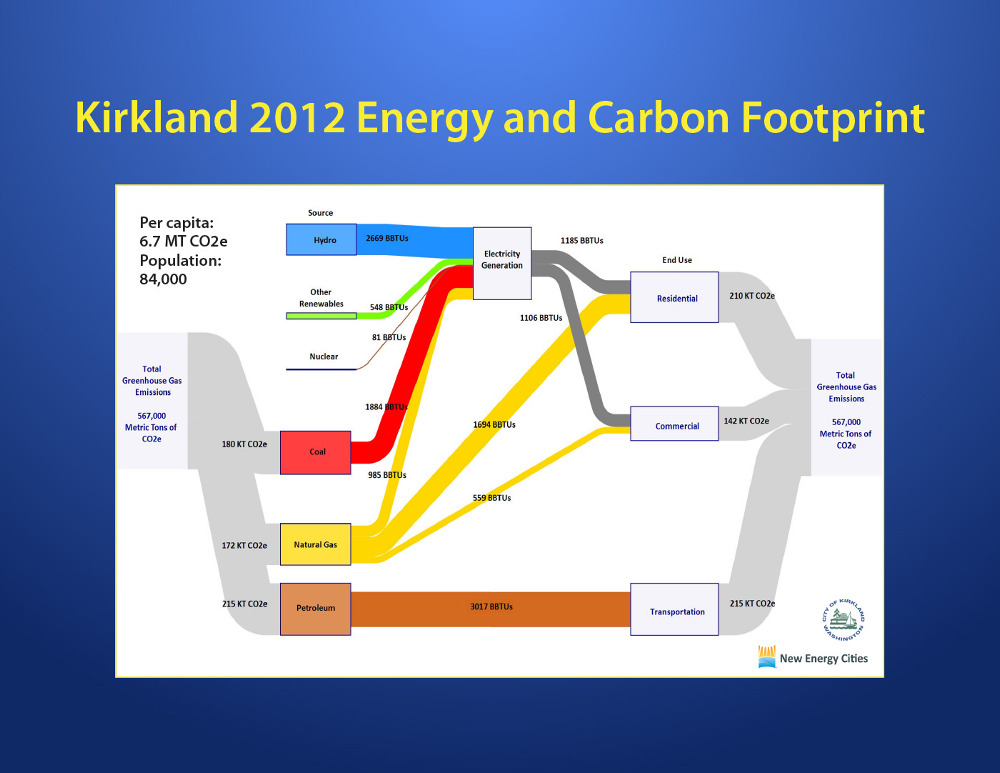

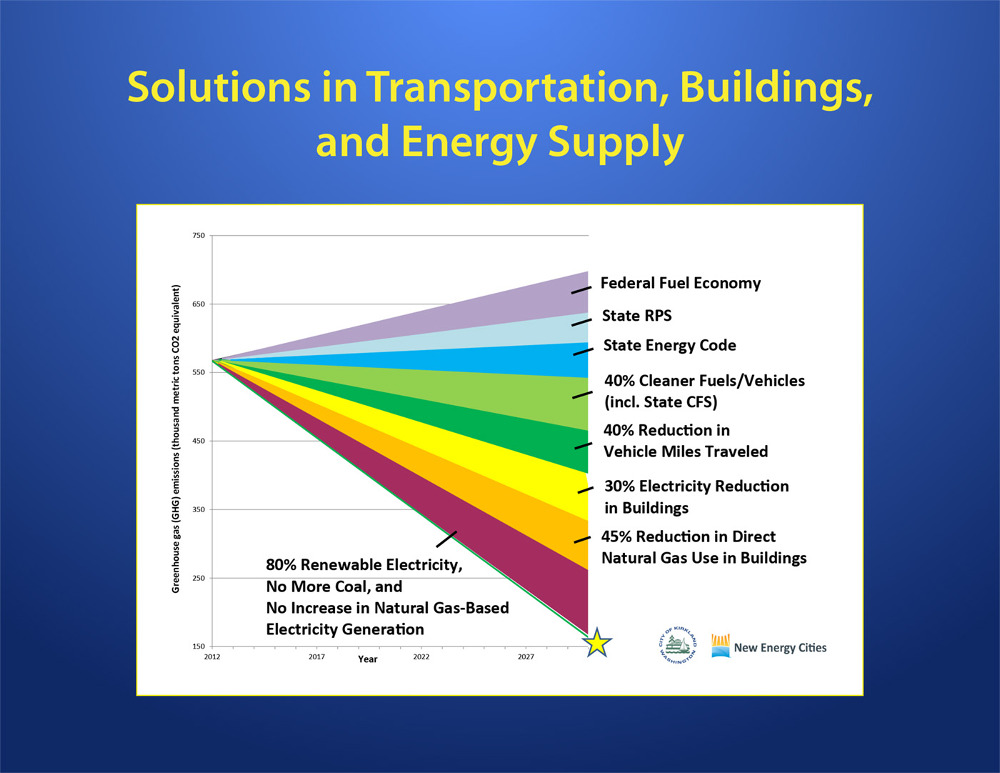

The carbon wedge above shows the sources of Kirkland energy and the different sectors (Residential, Commercial and Transportation) that use them.

Policy E-5.4: Pursue principles, pathways and policies as described in the current version of the King County Climate Change Collaborative (K4C) Joint County-City Climate Commitments and continue participation in regional collaboration in the K4C and the Regional Code Collaboration (RCC).

The Joint County-City Climate Commitments document provides suggested policies and the pathways that can help Kirkland, King County and other signatory cities work collaboratively to achieve the common goals relating to climate change. According to Climate Solutions, a consultant hired by the City, the three largest areas of emissions in Kirkland are residential and commercial energy use and transportation.

In order for Kirkland to make significant reductions in these areas and achieve its greenhouse gas emission reductions, it will be necessary to work with regional partners such as Puget Sound Energy, King County Metro and Sound Transit and State lawmakers. Puget Sound Energy provides gas and electricity for this region and will need to produce significantly more renewable energy for Kirkland to get to 80 percent renewable electricity usage. Transportation agencies will need to provide more service and use more renewable energy and the State must also adopt stricter fuel standards.

The Regional Code Collaboration (RCC), comprised of King County and participating cities, is working to revise building and energy codes with the intention of creating more energy efficient structures with lower GHG emissions. It is important for Kirkland to collaborate with other regional groups to increase the supply of clean, renewable energy for homes, businesses and vehicles because Kirkland is not in control of the regional energy supply. All of these efforts require strategic partnerships which can be bridged by the City’s continued advocacy and participation in the K4C and the RCC.

The graphics above show the categories of reductions necessary and the possible solutions for Kirkland to be on track with its greenhouse gas emission reductions by 2030.

Policy E-5.5: Advocate for comprehensive federal, state and regional science-based limits and a market-based price on carbon pollution and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Advocacy and support of legislative efforts to determine a path towards carbon pricing and other GHC emissions reduction strategies will be a role the City undertakes to effect changes in State requirements. This will be an important strategy for Kirkland as it has limited direct control over how much carbon is emitted in the City. The support of a mechanism for putting a price on pollutants, such as carbon and GHG emissions, could lead to an additional revenue source for the City to initiate programs to educate and incentivize citizens and businesses to reduce emissions.

Policy E-5.6: Support the adoption of a statewide low carbon fuel standard that gradually lowers pollution from transportation fuels.

Transportation is a major contributor to Kirkland’s and the region’s greenhouse gas emissions; therefore more efficient fuels will greatly reduce emissions.

Comprehensive advocacy and legislative effort will be necessary to communicate to local policy makers and state lawmakers the importance of making the fuel standards more stringent and therefore helping Kirkland achieve its emission reductions.

Policy E-5.7: Pursue 100 percent renewable energy use by 2050 through regional collaboration.

The Living Community Challenge establishes that a sustainable community will generate clean renewable energy and not use energy that contributes to additional greenhouse gas emissions. Since much of the energy that Kirkland uses is not renewable energy, this policy will require regional participation along with other K4C cities and legislative efforts to work with utility providers to increase production of clean renewable energy. This work should include working with local utilities and State regulators and other regional partners to develop a package of County and City commitments that support increasingly renewable energy and its use.

Local efforts to promote renewable energy production should be pursued. These can include community solar, community shared solar, green power community challenges, streamlined local renewable energy installation permitting, district energy, and renewable energy incentives for homeowners and businesses.

This policy lends support to the overall goal of Kirkland becoming carbon neutral or a net zero carbon community.

Policy E-5.8: Engage and lead community outreach efforts in partnership with other local governments, businesses and citizens to educate community about climate change efforts and collaborative actions.

In order to be successful with City and community climate change efforts, it will be important to communicate and work collaboratively with citizens, businesses and support efforts such as the Eastside Sustainable Business Alliance, Kirkland Green Business program, Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties, and the Kirkland Chamber of Commerce. Other means of outreach such as special presentations, workshops and joint campaigns or initiatives with the King County Climate Change Collaborative or other organizations will be helpful for educational purposes and building stakeholder support.

HEALTHY FOOD COMMUNITY

Food security planning can help address environmental and social justice issues, such as increasing access to healthy food choices in all neighborhoods and supporting hunger assistance programs. An emphasis on supporting the local food production economy can also have important economic, quality of life, and environmental benefits. Economic benefits include creating and sustaining living-wage jobs through food production, processing, and sales; improving the economic viability of the sales of local agriculture; and more efficiently using undeveloped parcels for urban agriculture. Kirkland can also foster environmental benefits and quality of life through programs that decrease food waste and reduce the miles food travels to store shelves and planning so that citizens have access to food during and after disasters.

Goal E-6: Support and encourage a local food economy.

Market at Juanita Beach Park

Policy E-6.1: Expand the local food production market by supporting urban and community farming, buying locally produced food and by participating in the Farm City Roundtable forum.

Within each local jurisdiction, demand for fresh food can be meet through allowances for local urban farming and with the encouragement of residents to grow at least some of their fresh produce in their yards or in community gardens. Community gardens can create a more inclusive community character and dialogue while individual gardens can promote a more direct connection to the environment for individuals.

Expanding food related uses within the City can help to create a more resilient community and sustainable economy. The City supports urban farming by making City parks available for farmer’s markets, such as Juanita Park, and community gardens, such as McAuliffe Park.

The City can also support local food production and distribution by participating in regional initiatives such the King County Local Food Initiative which has the stated goal of expanding the local food economy by:

• Taking advantage of an increasing interest among residents, tourists and food-related businesses in locally produced food.

• Encourage Community Supported Agriculture drop off locations in the City including food banks.

• Reducing barriers for farmers in getting their products to market.

• Preserving farmland from increasing development pressure as the region grows.

Policy E-6.2: Promote land use regulations that ensure access to healthy food.

The City has an important role to play in the creation of policies and regulations that emphasize the furthering of healthy lifestyles. Neighboring cities have faced the healthy communities issue in a variety of ways. The City of Seattle created a “Food Action Plan,” Des Moines chose to include “healthy eating,” while other cities like Federal Way chose to focus on the urban agriculture aspects of food, and Redmond focused on how community character and history play a role with food.

The City should consider commissioning its own food study to understand Kirkland’s food landscape and use data-driven results to determine how to best make changes in land use regulations to promote the access of healthy foods to all residents.

Policy E-6.3: Reduce environmental impacts of food production and transportation by supporting regionally produced food.

The City can play a role in reducing the environmental impacts of food production, processing and the distance that food must travel from the farm to table. This can be done by supporting actions that encourage the use of local and renewable energy, reductions in the use of other resources such as fossil fuels and water, and waste such as packaging of food. Some examples of other actions the City could take include:

• Restrict the use of excessive or environmentally inappropriate food packaging

• Promote composting at urban garden sites

• Support diversion of edible food from local businesses to food banks

• Promote the use of organic products, composting and farming techniques Citywide

• Promote water conservation and impacts of urban agriculture on surface and groundwater sources

• Support rainwater capture and innovative technologies to process greywater for safe use in urban agriculture

• Support agricultural technologies, processes and practices that protect soil and water resources

• Encourage the use of native or regionally produced edible plants and seeds

• Work with local and regional partners to educate citizens of the benefits of urban agriculture and stewardship

Policy E-6.4: Ensure food availability by planning for shortages during emergencies.

Food security is forecasted to become a major global issue in the coming decades, especially since food production and systems are intricately tied around the globe through internationally traded food commodities. Extreme weather events are already showing that food shortages resulting from climate change create a lack of food security for the people experiencing them, and inordinately affect lower income peoples around the globe.

At the local level, Kirkland can prepare for interruptions to food systems by promoting urban agriculture and coordinating with farms in outlying areas. The City of Kirkland has several programs in place such as:

|

|

Pea Patch Program |

|

|

Farmer’s Markets |

|

◦ Juanita Beach’s Friday Market |

|

|

◦ Wednesday Market |

|

|

|

The Victory Garden |

|

|

McAuliffe Park Urban Farm |

|

|

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) |

|

|

Edible Kirkland |

|

|

Community Gardens (privately held) |

|

|

Nourishing Network and Hopelink |

Regional cooperation models should be explored to develop a comprehensive food security plan that would be resilient to climate change and weather-related or disaster-oriented events. Better coordination with farms in our outlying areas can make Kirkland a more food secure City.

Figure E-1: Wetlands, Streams and Lakes

Figure E-2a: Landslide Susceptibility

Figure E-2b: Liquefaction Potential

Figure E-3: Topography

Figure E-4: Tree Canopy

Regional Ecosystem Analysis: Puget Sound Metropolitan Area – Calculating the Value of Nature, 1998, by American Forests, www.americanforests.org

.239120.JPG)

.239120.JPG)

.239120.JPG)