Chapter 14

Shoreline Restoration

SECTIONS:

14.2 Restoration Planning Requirements

14.5 Restoration Vision Statement

14.6 Restoration Goals, Priorities and Objectives

14.7 Restoration Opportunities

14.8 Existing and Ongoing Programs

14.11 Monitoring and Adaptive Management

14.13 Potential Funding Sources

14.15 Resource Links and References

14.1 Restoration Introduction

This restoration plan has been prepared in accordance with the Washington State Department of Ecology shoreline management guidelines. The guidelines direct local government review and updates of shoreline master programs. A significant feature of the guidelines is the requirement that local governments include within their shoreline master program, a “real and meaningful” strategy to address restoration of shorelines. WAC 173-26-186(8). The state guidelines emphasize that any development must achieve no net loss of ecological functions. The guidelines go on to require a goal of using restoration to improve the overall condition of habitat and resources and makes "planning for and fostering restoration" an obligation of local government. From WAC 173-26-201(2)(c):

Master programs shall also include policies that promote restoration of ecological functions, as provided in WAC 173-26-201(2)(f), where such functions are found to have been impaired based on analysis described in WAC 173-26-201(3)(d)(i). It is intended that local government, through the master program, along with other regulatory and non-regulatory programs, contribute to restoration by planning for and fostering restoration and that such restoration occur through a combination of public and private programs and actions. Local government should identify restoration opportunities through the shoreline inventory process and authorize, coordinate and facilitate appropriate publicly and privately initiated restoration projects within their master programs. The goal of this effort is master programs which include planning elements that, when implemented, serve to improve the overall condition of habitat and resources within the shoreline area of each city and county. [emphasis added]

WAC 173-26-2012(f) states further that “...master programs provisions should be designed to achieve overall improvements in shoreline ecological functions over time when compared to the status upon adoption of the master program.” For guidance on preparation of a Restoration Plan, the city looked to WAC 173-26-186, WAC 173-26-201(2)(c) and (f) and Restoration Planning and the 2003 Shoreline Management Guidelines, A Department of Ecology Report, as well as Systematic Approach to Coastal Ecosystem Restoration, developed by NOAA (Diefenderfer 2003) in addition to other resources listed at the end of this chapter. Restoration planning should be focused on tools such as economic incentives, broad funding sources such as Salmon Restoration Funding, volunteer programs, and other strategies. WAC 173-26-186(8)(c) and WAC 173-26-201(2)(f) (explaining the “basic concept” of restoration planning). Furthermore, because restoration planning must reflect the individual conditions of a shoreline, restoration planning provisions contained in the guidelines expressly note that a restoration plan will vary based on:

o Size of jurisdiction

o Extent and condition of shorelines

o Availability of grants, volunteer programs, other tools

o The nature of the ecological functions to be addressed

14.2 Restoration Planning Requirements

The Department of Ecology’s shoreline management guidelines WAC 173-26-201(2)(f) state that master program restoration plans shall consider and address the following subjects:

(i) Identify degraded areas, impaired ecological functions, and sites with potential for restoration;

(ii) Establish overall goals and priorities for restoration of degraded areas and impaired ecological functions;

(iii) Identify existing and ongoing projects and programs that are currently being implemented, or are reasonably assured of being implemented (based on an evaluation of funding likely in the foreseeable future), which are designed to contribute to local restoration goals;

(iv) Identify additional projects and programs needed to achieve local restoration goals, and implementation strategies including identifying prospective funding sources for those projects and programs;

(v) Identify timelines and benchmarks for implementing restoration projects and programs and achieving local restoration goals; and

(vi) Provide for mechanisms or strategies to ensure that restoration projects and programs will be implemented according to plans and to appropriately review the effectiveness of the projects and programs in meeting the overall restoration goals.

These requirements are intended to provide the framework to restore impacted, altered or missing ecological functions resulting from past development of the shoreline. The restoration planning is not intended to directly mitigate past or future development impacts on the City’s shorelines. Restoration is intended to improve the overall environmental conditions unrelated to upcoming projects developing in the shoreline environment. Nonetheless, restoration projects may leverage opportunities that result from development and restoration planning needs be aware of projects and programs so as to not duplicate efforts or potentially waste valuable resources.

14.3 What is Restoration?

The term restoration has a number of definitions, all of which share similar ideas. They often refer to the return of an area to a previous condition by improving the biological structure and function (Diefenderfer 2003). Examples of definitions of restoration put forth by various authors and agencies include bringing back a former, normal, or unimpaired state; a return to a previously existing natural condition; reestablishing vegetation; and returning a damaged ecosystem to its pre-disturbed state. The DOE shoreline master program guidelines state that:

“Restore,” “Restoration,” or “ecological restoration” means the reestablishment or upgrading of impaired ecological shoreline processes or functions. This may be accomplished through measures including but not limited to revegetation, removal of intrusive shoreline structures and removal or treatment of toxic materials. Restoration does not imply a requirement for returning the shoreline area to aboriginal or pre-European settlement conditions.

The Society of Wetland Scientists (2000) defines wetland restoration, which is similar to shoreline restoration, as actions taken in a converted or degraded natural wetland that result in the reestablishment of ecological processes, functions, and biotic/abiotic linkages and lead to a persistent, resilient system integrated within its landscape. In an effort to be clear and consistent in the discussion of restoration, five key elements of the concept of restoration are adapted from the Society:

1. Restoration is the reinstatement of driving ecological processes.

2. Restoration should be integrated with the surrounding landscape.

3. The goal of restoration is a persistent, resilient system.

4. Restoration should generally result in the historic type of environment but may not always result in the historic biological community and structure.

5. Restoration planning should include the development of structural and functional objectives and performance standards for measuring achievement of the objectives.

In this SMP, restoration is used broadly to include conservation and enhancement actions. Conservation is different from restoration as described above in that it protects areas relatively free of degradation. Enhancement, which improves shoreline functions, but may not result in restoration of underlying process, may be more viable than restoration in some instances.

14.4 Restoration Approach

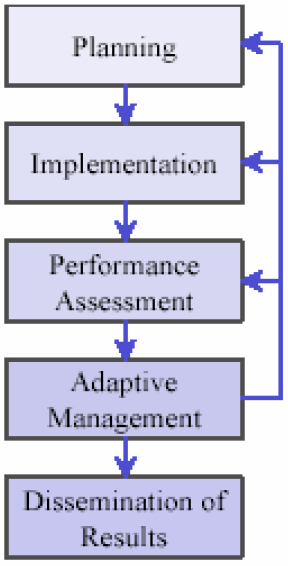

A systematic approach to restoration planning, implementation, and monitoring increases the accessibility of the plan and increases the long-term usability of the restoration framework. The five components of a systematic approach to a restoration project are planning, implementation, performance assessment, adaptive management, and dissemination of results. (Diefenderfer 2003).

Figure 1, above - Five Components of a Coastal Restoration Project. (Diefenderfer 2003).

NOAA’s Systematic Approach to Coastal Ecosystem Restoration is a usable guidance tool for each of these five components and states: “The planning process starts with a vision, a description of the ecosystem and landscape, and goals. A conceptual model and planning objectives are developed, a site is selected, and numerical models contribute to preliminary designs as needed. Performance criteria and reference sites are selected and the monitoring program is designed. Cost analysis involves budgeting, scheduling, and financing. Finally, documentation is peer reviewed prior to making construction plans and final costing.” (Diefenderfer 2003)

This restoration plan should be considered within this overall framework. The restoration chapter is designed to meet the requirements for restoration planning outlined in the DOE guidelines, in which restoration planning is an integrated component of shoreline master programs that include inventorying shoreline conditions and regulation of shoreline development. The restoration plan builds on the Port Townsend Shoreline Inventory and the Characterization Report (GeoEngineers 2004) which provide a comprehensive inventory and analysis of shoreline conditions in Port Townsend, including rating specific functions and process of each shoreline segment. Tables 1 through 5 in the Characterization Report summarize the baseline condition of ecological processes and functions.

This restoration plan provides a vision for ecological restoration, includes goals, objectives and opportunities. It also establishes city strategies for implementation, including recognition of existing and ongoing programs, and it provides a framework for long-term monitoring of shoreline restoration and shoreline conditions. While this restoration plan includes broad objectives, specific implementation measures, budgets, schedules, and individual monitoring programs will be needed for individual restoration projects as they occur.

To ensure that restoration goals are being achieved, it is important for the city to evaluate the performance effectiveness of this plan and to adapt to changing conditions. At a minimum, this restoration plan (as well as the entire Shoreline Master Program) will be reevaluated according to the schedule adopted by the state Legislature (the next update for Port Townsend would be in 2018 under the current schedule). It is recommended that the city conduct reevaluation of the success of the SMP and its restoration goals consistent with the Comprehensive Plan update schedule. At times of reevaluation, the inventory conditions and restoration metrics should be considered in comparison to the 2002-2005 conditions reviewed for this SMP. Updates to inventory information and the results of reevaluation processes should be disseminated to other restoration planning agencies to facilitate regional monitoring of environmental conditions.

Adaptive management is the process of continually improving management policies and practices to respond to results. Shoreline planning is iterative. As data is gathered and compared to past years’ data, one will be able to come to a clearer understanding of environmental processes and stressors. As understanding increases, the city will have the opportunity to adjust policies, regulations and restoration priorities to adapt to changes in conditions and information. At a minimum, the city will be required to take corrective actions if the mandate of no net loss of shoreline ecological resources is not being met.

The Point No Point Treaty Council (PNPTC) has been actively working on a shoreline analysis of historical changes and their root causes of Hood Canal and the Strait, including the habitat complexes within the Port Townsend jurisdiction. Though the document is not complete, it will be in the near future and may add a new layer of analysis and recommendations for shoreline restoration. Future restoration projects and planning should consider the context provided by the PNPTC effort and other environmental studies that might be completed in the future.

14.5 Restoration Vision Statement

The vision statement establishes the overarching idea of the future restored ecosystem and provides a basis for the framework, including the restoration goals and objectives. The Characterization Report identifies impaired ecological processes and functions. Tables 1 through 5 of the Characterization Report summarize nineteen processes and functions for five shoreline segments (i.e., 19x5=95 rankings). Of the 95 opportunities, only six were found to be properly functioning in GeoEngineers’ assessment. The remaining were “not properly functioning” or “at risk.” The implications are clear: with the vast majority of processes and functions on Port Townsend shorelines impaired based on the analysis, policies that “promote restoration” of these ecological functions must be included in the master program. This vision statement seeks to make clear the intent of addressing ecological restoration.

Restoration Vision: Degraded ecological processes and habitats of the Port Townsend shoreline are restored so that, when combined with protection of existing resources, a net improvement to the shoreline ecosystem is obtained to benefit native fish and wildlife and the people of Port Townsend. Restoration occurs over time through a combination of public and private ventures and leverages opportunities presented by shoreline development in a way that enhances the environment and is compatible with planned shoreline uses.

14.6 Restoration Goals, Priorities and Objectives

The goals and objectives included here are developed for the Port Townsend shoreline and are consistent with the basin wide general recommendations related to nearshore habitats in the Watershed Management Plan for the Quilcene-Snow Water Resource Inventory Area 17 (October 28, 2003), which includes Port Townsend. Overarching goals for restoring the Port Townsend shoreline are to: improve water quality, restore degraded and lost habitat and corridors, and improve connectivity of the shoreline environments in terms of both space and time.

These goals identify the direction of needed improvement. Objectives identify specific actions, ideally measurable, that can be taken to achieve the stated goals. For example, to meet the goal of improving water quality, an objective would be to remove creosote pilings. By translating the restoration goals into objectives, the objectives for Port Townsend restoration are:

a. Protect naturally eroding bluffs

b. Protect and restore native vegetation

c. Protect and restore wetlands and restore salt marsh habitat

d. Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes

e. Manage and treat stormwater and wastewater properly

f. Remove/replace unused creosote pilings

These objectives assist with defining actions or projects to restore the natural processes and ecological functions identified in the Characterization Report as not properly functioning.

Opportunities and strategies are then identified as means of implementing the objectives. At this level, no measurable performance standards are applied to goals. For example, the overall goal is to improve water quality to meet the vision of a restored ecosystem, not to improve it by "X" amount. Individual restoration projects that may be implemented as part of this plan are expected to include specific measurable goals.

In accordance with the state guidelines, it is also valuable to establish general priorities. Controlling environmental factors (such as hydrology, sediment type, etc.) provide the foundation for habitat structures (i.e., species and their abundance), and the structure supports habitat functions (i.e., production, food support, rearing, etc.). (Thom. 2003) That is, restoration of habitat functions may be ineffective if habitat structures and controlling factors are not also restored.

While Thom states, “There is no universally accepted method for setting priorities for nearshore sites for restoration or for determining what strategies are best applied to each site. We have found that restoration of controlling factors is the key to successful and long-term restoration.” general priorities for shoreline management could follow mitigation sequencing. That is, conservation and preservation should be the highest priority, followed by avoidance, followed by restoration, then enhancement and monitoring. Overall priority should be given to protection and restoration of natural processes that are needed to support ecosystem and habitat functions.

Thorough scientific evaluation and prioritization of all restoration opportunities was not feasible for this SMP. However, Port Townsend can work with the ecologist at the Hood Canal Coordinating Council and other regional scientists to help identify restoration of the greatest importance according to scientific criteria.

Ultimately, priorities will be opportunistic based on site access, available funding, and feasibility. In section 14.10 of this chapter, project evaluation is provided to aid in evaluating projects. Of the restoration opportunities listed, stormwater system improvements to address untreated stormwater outfalls may be the most readily feasible for the City due to public control of the system and the need to also address clean water planning requirements to meet EPA standards.

Table 14.6-1 shows the relationship of the goals, objectives, natural processes and ecological functions. The first column shows the goals, the second column shows the objectives associated with those goals and the third column shows the natural process and ecological function that will be enhanced by completing the objectives. Objectives are found under multiple goals affecting different natural processes and ecological functions. Potential metrics for monitoring each objective are listed in the right hand column. Opportunities for implementation are listed in Table 14.7-1 in the next section.

|

Restoration Goal |

Objective |

Natural Process |

Potential Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ecological Function |

|||

|

Improve water quality |

Remove/replace unused creosote pilings; remove creosote beach logs |

Sediment Transport |

# creosote pilings water quality measurements |

|

Toxic Compound Removal Support Vegetation |

|||

|

Protect and restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat |

Hydrologic Processes Sediment Transport Nutrients |

wetland acreage wetland functions wetland ratings water quality measurements |

|

|

Water Storage Sediment Storage Toxic Compound Removal Nutrient Removal |

|||

|

Manage and treat stormwater and wastewater properly |

Hydrologic Processes Sediment Transport Nutrients |

water quality measurements storm flows |

|

|

Water Storage Sediment Storage Toxic Compound Removal Nutrient Removal |

|||

|

Protect and restore native vegetation |

Hydrologic Processes Nutrients |

% impervious surface in basin acreage of vegetation water quality measurements |

|

|

Water Storage Sediment Storage Nutrient Removal Toxic Compound Removal |

|||

|

Remove intertidal fill |

Sediment Transport |

acreage or number of restored/remaining impaired areas |

|

|

Water Storage Sediment Storage Nutrient Removal |

|||

|

Restore degraded and lost habitat and corridors |

Protect and restore native vegetation |

Sediment Transport Vegetation Nutrients Habitat |

acreage of vegetation degree of diversity species supported connectivity/areas of isolation extent of tree canopy |

|

Support Vegetation Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Rearing Habitat Resting Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors Food Production Food Delivery |

|||

|

Protect and restore wetlands salt marsh habitat, and estuarine and lagoon functions |

Hydrologic Processes Sediment Transport Vegetation Nutrients Habitat |

wetland acreage wetland functions wetland ratings |

|

|

Support Vegetation Organic Material Availability Rearing Habitat Resting Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors Food Production Food Delivery |

|||

|

Protect naturally eroding bluffs, sand spits and accretion land forms |

Sediment Transport Vegetation Habitat |

acreage of vegetation in bluff areas linear feet of bulkhead |

|

|

Support Vegetation Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Beach Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors |

|||

|

Restore degraded and lost habitat and corridors (cont’d) |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

Sediment Transport Vegetation Nutrients Habitat |

acreage or number of restored/remaining impaired areas linear feet of bulkhead |

|

Support Vegetation Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Rearing Habitat Resting Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors Food Production Food Delivery |

|||

|

Manage and treat stormwater and wastewater properly |

Hydrologic Processes Sediment Transport Nutrients |

water quality measurements storm flows |

|

|

Water Storage Sediment Storage Toxic Compound Removal Nutrient Removal |

|||

|

Improve connectivity of the shoreline environments in terms of both space and time |

Protect and restore native vegetation |

Hydrologic Processes Sediment Transport Vegetation Nutrients Habitat |

acreage of vegetation connectivity/areas of isolation extent of tree canopy linear feet of bulkhead |

|

Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Rearing Habitat Resting Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors Food Delivery |

|||

|

Protect and restore wetlands, salt marsh habitat and estuarine and lagoon functions |

Hydrologic Processes Sediment Transport Vegetation Nutrients Habitat |

wetland acreage wetland functions wetland ratings connectivity/areas of isolation |

|

|

Support Vegetation Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Rearing Habitat Resting Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors Food Production Food Delivery |

|||

|

Remove intertidal fill/ restore beach deposits and processes |

Sediment Transport Vegetation Nutrients Habitat |

acreage of restored/remaining impaired areas shoreline connectivity/areas of interruption |

|

|

|

Support Vegetation Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Rearing Habitat Resting Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors Food Production Food Delivery |

|

|

|

Protect naturally eroding bluffs, sand spits and accretion land forms |

Sediment Transport Vegetation Habitat |

acreage of vegetation in bluff areas linear feet of bulkhead |

|

|

Support Vegetation Woody Debris Recruitment Organic Material Availability Beach Habitat Predation Avoidance Habitat Migration Corridors |

14.7 Restoration Opportunities

Table 14.7-1 lists specific opportunities for each shoreline segment that have been identified in the Inventory, Characterization Report, and through other shoreline planning processes. These are opportunities for restoration that correspond to the state restoration goals and objectives. Opportunities listed by shoreline segment are in the left hand column. The second column lists the related restoration objective. Identified restoration activities and monitoring activities, where known, are listed in the two right hand columns.

This is an extensive list that likely exceeds near term funding opportunities, and yet, is not exhaustive. Additional restoration opportunities may continue to be identified through local and regional shoreline monitoring and planning actions. Further discussion of ongoing programs, implementation strategies, and project evaluation to determine appropriate priority and selection is provided in the sections following the table. As such, Table 14.7-1 is based on a point of time and it is expected that actual restoration opportunities and priorities will evolve over time as restoration projects are completed and new information becomes available. The City may periodically identify additional restoration opportunities that are consistent with the objectives of this restoration chapter.

|

Restoration Opportunity |

Priority |

Restoration Objective |

Restoration Activity |

Monitoring Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Southern Shoreline |

||||

|

Treat stormwater entering Port Townsend Bay from developed areas |

High |

Manage and treat stormwater and wastewater properly |

Ongoing implementation of the Stormwater Management Manual for Puget Sound Stormwater system improvements as street improvements are constructed |

Water quality monitoring in bay |

|

Investigate/Study Options for best ecosystem benefits of restoring wetlands adjacent to Larry Scott Memorial Trail with Port Townsend Bay |

Medium |

Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat |

No ongoing activity identified |

City and NWI GIS mapping |

|

Remove pilings at Indian Point |

Low |

Remove unused creosote pilings |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove or replace creosote piles whenever possible to eliminate bioaccumulation of contaminates in marine ecosystem, including old ferry dock pilings |

Low-High (depending on circumstances: presence of creosote, impact on littoral drift) |

Remove unused creosote pilings |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove riprap on either side of Union Wharf to provide pocket beaches |

Low |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Nourishment of pocket beaches |

Low |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove concrete at John Pope Marine Park |

Medium |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of shoreline |

|

|

|

processes |

|

armoring |

|

Remove or reconfigure Tidal Clock (Jackson Bequest sculpture) to allow tidal movement |

Low |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Provide fixed anchor buoys to avoid transient boat anchorage damage to eelgrass |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors |

Jefferson County Marine Resources Committee (MRC) pilot project |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Restore eel grass beds where possible |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors |

NWMC eelgrass restoration project |

Long-term monitoring is associated with the specific project |

|

Fill dredged area seaward of Port Townsend Plaza to facilitate colonization of eelgrass |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove or restore derelict and unused structures such as the old Quincy Street ferry dock and the Wave Gallery |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove/reduce impact of artificial night-lighting effects to intertidal habitat |

Low |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Restore native marine riparian vegetation where possible |

Medium to High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors |

No ongoing activity identified |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Remove remaining train trestle |

High |

Remove unused creosote pilings and improve littoral drift |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Restore vegetation at Point Hudson and relocate RV parking area away from point |

High |

Protect and restore native vegetation |

see Port of Port Townsend Comprehensive Scheme for planned improvements to Point Hudson |

Port of Port Townsend Comprehensive Scheme and EIS provides environmental information about Point Hudson and proposed improvements |

|

Eastern Shoreline |

||||

|

Remove pilings at Fort Worden near lighthouse |

Low |

Remove unused creosote pilings |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Use beach nourishment to replace eroded sediments, if possible |

Low |

Removal intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Move lighthouse and remove related pavement, structures, riprap, gabions, and ecoblocks |

High |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes, sand spits and accretion land forms |

Ongoing discussions with Coast Guard and State Park |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Consider opening southern end of the State Park marina breakwater |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors; improve littoral drift, allow juvenile salmon passage along the shallow nearshore habitats of the boat basin area |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Feed more sediments to the beach on the east side of the marina |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors; documented forage fish spawning beach |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Treat, store, and redirect stormwater run-off that runs through Chetzamoka Park |

High if chlorine or stormwater contaminants present |

Treat stormwater properly |

Ongoing implementation of the Stormwater Management Manual for Puget Sound Stormwater system improvements as street improvements are constructed |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Removal of riprap along Chetzamoka Park |

Medium |

Protect naturally eroding bluffs |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of shoreline armoring |

|

Protection or acquisition of Jefferson County Tree Project Property near Chetzamoka Park |

Medium |

Protect naturally eroding bluffs |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove bulkhead |

Medium |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of shoreline armoring |

|

Provide education incentives to encourage tree planting and retention |

Medium |

Protect naturally eroding bluffs |

No ongoing activity identified |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Restore native marine riparian vegetation where possible |

Medium to High depending upon location |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors Protect and restore native vegetation |

No ongoing activity identified |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Northern Shoreline |

||||

|

Remove pilings at Fort Worden near lighthouse |

Low |

Remove unused creosote pilings |

No ongoing activity identified |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Remove riprap on northern shore of Fort Worden |

High |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes, sand spits and accretion land forms |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of shoreline armoring |

|

Remove unused concrete boat ramp at North Beach County Park |

High |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of boat ramps |

|

Remove bulkheads |

Medium |

Remove intertidal fill/restore beach deposits and processes |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of shoreline armoring |

|

Provide education incentives to encourage tree planting and retention |

Medium |

Protect naturally eroding bluffs |

No ongoing activity identified |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Homeowner education and encourage bulkhead removal where possible |

Medium |

Protect naturally eroding bluffs |

No ongoing activity identified |

City has GIS mapping of shoreline armoring |

|

Restore native marine riparian vegetation where possible |

High |

Protect and/or restore nearshore habitat and corridors Protect and restore native vegetation |

No ongoing activity identified |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Lake Shoreline - Chinese Gardens |

||||

|

Restore native riparian forested buffer |

High |

Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat Protect and restore native vegetation |

No ongoing activity identified |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Treat stormwater entering Chinese Gardens from developed areas |

High |

Manage and treat stormwater and wastewater properly |

Ongoing implementation of the Stormwater Management Manual for Puget Sound Stormwater system improvements as street improvements are constructed |

Water quality monitoring in straights |

|

Investigate/study opportunities for restoration including possible Reconnection of wetland with Strait of Juan de Fuca |

High |

Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat |

No ongoing activity identified |

City and NWI GIS mapping |

|

Lake Shoreline - Kai Tai |

||||

|

Removal of invasive species |

High |

Protect and restore native vegetation Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat |

Ongoing Kai Tai planning process |

No ongoing monitoring identified |

|

Replant shoreline with native vegetation |

High |

Protect and restore native vegetation Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat |

Ongoing Kai Tai planning process |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Restore native riparian forested buffer |

High |

Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat Protect and restore native vegetation |

Ongoing Kai Tai planning process |

2005 aerial photograph |

|

Investigate/Study opportunities for restoration including possible Restoration of tidal flow between the lagoon and saltwater |

High |

Protect and/or restore wetlands and salt marsh habitat |

No ongoing activity identified |

City and NWI GIS mapping |

|

Treat stormwater entering Kah Tai from developed areas |

High |

Manage and treat stormwater and wastewater properly |

Ongoing implementation of the Stormwater Management Manual for Puget Sound Stormwater system improvements as street improvements are constructed |

Water quality monitoring in bay |

14.8 Existing and Ongoing Programs

The following list of agencies and organizations with nearshore interests is by no means complete. It does, however, include those agencies and organizations that appear to have the most interest in nearshore areas and restoration in and around the City of Port Townsend.

Hood Canal Coordinating Council (HCCC): Summer Chum Salmon Recovery Plan

The Hood Canal Coordinating Council, a “Watershed Based Council of Governments”, was established in 1985 under the Inter-local Cooperation Act (RCW 39.34) and was incorporated in 2000 as a “Non-profit, Public Benefit Corporation” (RCW 24.03.) The Council was established in response to community concerns about water quality problems and related natural resource issues in the watershed. The Staff to the Council are focusing their efforts on three activities:

a. Salmon recovery planning and monitoring (primarily summer chum salmon, Chinook salmon, and bull trout)

b. Salmon habitat projects (freshwater and marine)

c. Water quality (primarily the Hood Canal low dissolved oxygen problem)

In 1998, the Washington State Legislature passed the Salmon Recovery Act (HB 2496, now codified along with several amendments under RCW 77.85), to address the decline of salmon in this state. HB 2496, and subsequent legislation (SB 5595) set up the Salmon Recovery Funding Board (SRFB), which is responsible for implementation and oversight of the Salmon Recovery Act. The SRFB provides funding for salmon recovery projects located throughout Washington State. The Hood Canal Coordinating Council serves as the Lead Entity for Hood Canal and eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca as set forth in the Salmon Recovery Planning Act. Individuals and organizations interested in participating in salmon recovery projects can find more information on the grant process and pertinent programs such as the Marine Riparian Initiative as www.hccc.wa.gov.

Jefferson County Marine Resources Committee

In 1998, passage of the Northwest Straits Marine Conservation Initiative established the Northwest Straits Commission and seven Marine Resource Committees, including the Jefferson County Marine Resource Committee (Jefferson MRC). The Jefferson MRC is a citizen-based effort to identify regional marine issues, foster community understanding and involvement, recommend positive action and develop support for various protection and restoration measures. The Jefferson MRC works toward fulfilling the following performance standards:

a. Broad county participation in MRCs

b. Achieve a scientifically-based, regional system of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

c. A net gain in highly ecologically productive nearshore, intertidal and estuarine habitat in the Northwest Straits, and no significant loss of existing, high-value habitat; improve state, tribal, and local tools to map, assess, and protect nearshore habitat and prevent harm from upland activities

d. Net reduction in shellfish harvest areas closed due to contamination

e. Measurable increases in factors supporting recovery of bottom fish (such as rockfish)--including numbers of fish of broodstock size and age, average fish size, and abundance of prey species--as well as sufficient amounts and quality of protected habitat

f. Increases in other key marine indicator species (including those identified in the 1997 West report on Puget Sound marine resources)

g. Coordination of scientific data (for example, through the Puget Sound Ambient Monitoring Program), including scientific baseline, common protocols, unified GIS, and sharing of ecosystem assessments and research

h. Coordinate with the Puget Sound Action Team and other entities on an effective outreach and education effort with measurements of the numbers of people contacted as well as changes in behavior.

In an attempt to reduce boating impacts to our local eelgrass, the Jefferson County Marine Resources Committee (MRC) will began a pilot project this year to inform boaters about the potential damage their anchors can cause, and encourage them to drop anchor outside the eelgrass areas. The MRC is a citizen-based advisory work group of the Board of County Commissioners that was first formed in 1999 and is tasked with pursuing eight performance benchmarks for improved marine resources. This group has received funds from the Northwest Straits Commission to place six to eight seasonal marker buoys just beyond the outer edge of the eelgrass meadows in Port Townsend Bay, between Point Hudson and the Washington State Ferry Terminal. These buoys identify the area as a voluntary anchor-free zone with a "no anchor" symbol in order to help protect the eelgrass meadows. The program will be explained through signs installed at appropriate places on the shore and through distribution of brochures.

North Olympic Salmon Coalition (NOSC)

NOSC is a non-profit community based salmon recovery organization which provides funding, guidance, technical assistance, and ongoing support for salmon habitat restoration and enhancement. NOSC is one of the 14 Regional Fisheries Enhancement Groups throughout the state of Washington. The region includes the watersheds along the coast of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, from the Hood Canal Bridge west to Neah Bay. NOSC works cooperatively with the Washington Dept of Fish and Wildlife, Conservation Districts, Tribal Fisheries, schools, community organizations, volunteers and private landowners.

Northwest Maritime Center

The NWMC eelgrass restoration site is located in the waters of Port Townsend Bay at 400 Water Street, Tidelands 16. Upland portions of the site can be legally described as Block 4 and vacated Water Street, Original Townsite of Port Townsend, City of Port Townsend, and Jefferson County, Washington. Section 1, SW1/4, Township 30N, Range 1W. Eelgrass restoration at the NWMC dock is proposed to occur during the summer of 2004. Roughly 4,250 shoots of eelgrass will be planted covering approximately 4,300 square feet (400m2), essentially connecting the two existing eelgrass beds. This effort will be done by hand and will take three to five divers between three to five days to complete. As part of long-term monitoring, dive surveys, mapping, and monitoring to assess the recolonization of the beds is being conducted.

Puget Sound Action Team

The Puget Sound Action Team is a partnership that defines, coordinates and implements Washington State’s environmental agenda for Puget Sound. This partnership is the central coordinator for the state’s vision and collective efforts in Puget Sound. The purpose of the Puget Sound Action Team partnership is to protect and restore the Puget Sound and its spectacular diversity of life now and for future generations. The legislature created the Puget Sound Action Team in 1996 as the state’s partnership for Puget Sound. A Strategic Framework guides the Action Team partnership’s work.

The Puget Sound Council consists of representatives from a variety of important interests from the Puget Sound region. The Puget Sound Council provides advice and guidance to help steer the Action Team. It has representation from business, agriculture, the shellfish industry, environmental organizations, local governments, tribal governments, and the Washington state legislature. The Puget Sound Council advises the Action Team on work plan priorities and tracks the progress of state and local agencies in implementing the plans. The Council also recommends changes to the Puget Sound Water Quality Management Plan to address emerging issues.

The Action Team staff provides the necessary professional and technical services to ensure the team’s success. Action Team staff help guide the implementation of the Puget Sound Water Quality Management Plan and work with tribal and local governments, community groups, citizens and businesses and state and federal agencies to develop and carry out two-year work plans. The work plans outline measurable results, as well as needed actions to improve the water quality and habitats for fish, marine animals and other aquatic life in Puget Sound.

Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project (PSNERP)

PSNERP is a cooperative effort among government organizations, tribes, industries, and environmental organizations to preserve and restore the health of Puget Sound’s nearshore that generally runs from the top of bluffs on the land across the beach to the point where light penetrates the Sound’s water sufficient to support attached marine vegetation (approximately 30 feet deep).

A General Investigation Reconnaissance Study conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2000 identified a direct link between properly functioning (healthy) nearshore habitat and the physical condition of the shoreline. The study identified four areas that need restoration and improvement:

1. Restoring shoreline processes to a more natural state,

2. Providing beaches with essential sand and gravel materials,

3. Removing, moving, and modifying artificial structures (bulkheads, rip rap, etc.), and

4. Using alternative measures to protect shorelines from erosion.

The timeframe for implementing projects is longer term, with projects beginning in 2008. By June 2006, PSNERP will produce a strategic needs assessment for comprehensive, geo-spatially explicit, process-based restoration of Puget Sound’s nearshore ecosystem. The PSNERP Science Team is working to narrow the uncertainty inherent in restoration, by improving our understanding of the most critical restoration needs at various scales of analysis in Puget Sound. To do so, PSNERP is reviewing and synthesizing a number of existing key data sets, collecting new information and adopting the most effective theories on the link between landscape ecology and restoration.

The current understanding of relationships between nearshore processes, structures and functions is illustrated in a nearshore conceptual model. This conceptual model continues to be refined as scientists test new hypotheses about nearshore processes, structure and function. Preliminary outputs of this analysis is informing those engaged in nearshore habitat restoration as part of their species recovery plans through this web site and guidance to the Salmon Recovery Funding Board. In turn, actions taken by salmon recovery lead entities may serve to evaluate hypothesized relationships between restoration actions and effects on ecosystem processes and salmon populations. It is expected that over time, the relationship between local species-specific efforts and regional process-based approaches will converge to the point that the restoration goals identified by species recovery entities and those of PSNERP are one and the same for many projects. Collaboration and sharing of resources will serve to bring about a common endpoint as the ecological integrity of Puget Sound is improved to the benefit of salmon, shellfish, marine birds, and other components of the ecosystem.

Puget Sound Nearshore Policy Group

Staff to the Puget Sound Action Team (PSAT) partnership has convened a regional group to conduct a policy discussion that sets a vision for salmon recovery in Puget Sound’s nearshore and marine environments. This vision will lead to actions that protect and restore Puget Sound’s shorelines, marine areas and estuaries for salmon recovery.

This high-level policy group is central to development of a nearshore chapter in Shared Strategy’s salmon recovery plan for Puget Sound. This group is working to establish policy direction and identify needed commitments to actions that will protect and restore Puget Sound’s shorelines, marine areas, and estuaries for salmon recovery. This nearshore chapter will address regional threats to the nearshore environment and regional-scale management opportunities.

The specific objectives of the nearshore policy group are to:

1. Develop a set of regional strategies for salmon recovery in the nearshore;

2. Identify needed commitments for actions and pathways to gain those commitments;

3. Develop prescriptions for additional activities that should occur to protect and restore nearshore and marine ecosystems in the Puget Sound region; and

4. Develop an overall vision of nearshore and marine contributions to salmon recovery and integrate this vision with all other chapters of the Shared Strategy’s recovery plan.

The nearshore policy group has technical support from PSAT staff members who are working with regional experts and other individuals involved in developing planning area chapters. Staff members and others are working to assess and analyze relationships among management actions that might be needed to protect and restore the nearshore and marine ecosystem processes and functions that will support viable salmon populations.

Puget Sound Technical Recovery Team (TRT)

The Puget Sound Technical Recovery Team provides the overall scientific conceptual approach for assessing salmon recovery planning. This approach identifies the four characteristics of a population and their role in maintaining population viability. These characteristics are abundance, productivity, spatial structure and diversity. TRT liaisons help watershed groups implement their technical approach to ensure that it is consistent with the logic laid out in the Watershed Guidance. Kurt Fresh, biologist with NOAA Fisheries, and other scientists also support watersheds in applying the TRT guidance document to the nearshore component of their draft habitat plans.

Shared Strategy for Puget Sound

The Shared Strategy is a collaborative effort to protect and restore salmon runs across Puget Sound. Shared Strategy engages local citizens, tribes, technical experts and policy makers to build a practical, cost-effective recovery plan endorsed by the people living and working in the watersheds of Puget Sound. To accomplish this, Shared Strategy partners have designed a work program that calls for draft chapters of recovery plans by June 2004 and for final chapters by June 2005.

Shared Strategy staff support local watershed planning areas in developing policy and technical approaches to recovery planning. These approaches will result in a chapter that contains actions and commitments. Shared Strategy staff support watersheds in obtaining the additional support necessary for them to develop their chapter. Shared Strategy staff also work with the Action Team to support the development of a Puget Sound-wide nearshore chapter.

Washington Dept of Fish and Wildlife, Summer Chum Salmon Conservation Initiative: A Plan to Recover Summer Chum Salmon

The goals of the chum salmon recovery plan is to protect, restore and enhance the productivity, production and diversity of Hood Canal summer chum salmon and their ecosystems to provide surplus production sufficient to allow future directed and incidental harvests of summer chum salmon. The plan focuses primarily on harvest and hatchery issues for summer chum salmon, though it does not document physical habitat conditions in the natal summer chum watersheds and sub-estuaries.

WSU Shore Stewards Program / Water/Beach Watchers

WSU will be starting a Shore Stewards Program as part of the Water/Beach Watchers in 2005. It is a one year old program piloted by WSU Island County Beach Watchers. It provides education and best practices for shoreline landowners, and participants receive a metal Shore Stewards sign for their property. The WSU Regional Water Quality Team applied for grant funding to PSAT and will be partnering with WSU and WA Sea Grant in Mason and Kitsap counties to do a coordinated program all along Hood Canal. This has been described as the best design for an on-going stewardship program to help improve the low dissolved oxygen situation in the Canal.

Watershed Planning (WRIA 17)

Watersheds often encompass broad land areas and cross various governmental jurisdictions. The Watershed Management Act created a mechanism to focus water-related planning on a local, watershed basis by forming the Planning Unit, composed of various interests and governments. Included in the new administrative body are counties, municipalities, utilities and Tribal Governments, collectively knows as Initiating Governments. The composition of the Planning Unit must include a wide range of water resource interests and representatives of state, county, and tribal governments whose policies and resources may be affected by the proposed plan. The purpose of the Planning Unit is to formulate a plan containing recommendations on water quality and quantity management, protection and restoration of instream flows, protection of fish habitat and alternative strategies for managing water, to be sent to local and state governments for adoption. The Planning Unit instituted two subgroups; the Steering Committee, to help it move forward with administrative issues; and a Technical Committee to sort through the details of resource data required to make informed water management decisions. The final WRIA 17 Plan is now available on their website.

14.9 Strategies

This section discusses programmatic measures for the City of Port Townsend designed to foster shoreline restoration and achieve a net improvement in shoreline ecological processes, functions, and habitats. With projected budget and staff limitations, the City of Port Townsend does not anticipate leading most restoration projects or programs. However, the City’s SMP represents an important vehicle for facilitating and encouraging restoration projects and programs that could be led by private and/or non-profit entities. The discussion of restoration mechanisms and strategies below highlights programmatic measures that the City could implement, as well as parallel activities that would be led by other governmental and non-governmental organizations.

Restoration Demonstration Project

A small demonstration restoration project that included a variety of techniques could be completed by the City as an example for others. The City could also identify a set of good demo restoration projects (which have broad public support), then actively solicit entities to implement one or more of them.

Additionally, the City could work with existing programs such as the HCCC Marine Riparian Initiative to leverage funding and efforts where available to implement smaller scale demonstration projects.

Volunteer Coordination

Another way the city could accomplish restoration projects is by using community volunteers. Volunteers could be recruited for project implementation and monitoring and the city would provide equipment and expertise. The city would also need to fund a volunteer coordinator to organize projects, solicit various environmental groups and individual volunteers to complete the projects and partner or coordinate with other government entities on projects.

Regional Coordination

The City should consider formally joining and taking an active role in the Hood Canal Coordinating Council, an inter-governmental organization facilitating freshwater and shoreline habitat restoration for salmon recovery, rather than attempting to duplicate its activities. The city should also look for other opportunities for involvement in regional restoration planning and implementation.

Capital Facilities Program

The City should develop shoreline restoration as a new section of the city’s Capital Facilities Program, even if not immediately funded, to ensure that they are considered during the City’s budget process. Some of the opportunities listed that may be prime candidates for immediate consideration due to interest and potential outside support are:

• Removal, in cooperation with the County, of the relic concrete boat ramp at North Beach Park, a County park, on the north shoreline near Chinese Gardens. Rough cost estimate: $20,000

• Removal of remaining train trestle at the west end of the Kai Tai Trough and near the start of the Larry Scott Trail. Rough cost estimate: $100,000

• Re-establishment of the connectivity of the marine shoreline with the associated wetland at the west end of the Kai Tai Trough and near the start of the Larry Scott Trail. Rough cost estimate: $250,000

Development Opportunities

When shoreline development occurs, the City should look for opportunities to conduct restoration in addition to minimum mitigation requirements.

Development may present timing opportunities for restoration that would not otherwise occur and may not be available in the future.

Mitigation may also allow for the “banking” for opportunities.

In certain cases, on-site mitigation opportunities are limited due to building site constraints, limited potential ecological gains, or other site-specific factors. In these instances, the City shoreline administrator may identify an off-site restoration site that could be contributed in lieu of on site mitigation.

Development Incentives

Provide development incentives for restoration that might include the waiving of some or all of development application fees or waiving city-required infrastructure improvement fees. This could serve to encourage developers to try to be more imaginative or innovative in their development designs to include more access and preservation.

Tax Relief / Fee System

Consider a tax/fee system to directly fund shoreline restoration measures. One possibility is to have the City work with the county to craft a preferential tax incentive through the Public Benefit Rating System administered by the County under the Open Space Taxation Act (RCW 84.34) to encourage private landowners to preserve natural shore-zone features for "open space" tax relief. DOE has published a technical guidance document for local governments who wish to use this tool to improve landowner stewardship of natural resources. More information about this program can be found at http://www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/99108.html. The guidance in this report provides "technically based property selection criteria designed to augment existing open space efforts with protection of key natural resource features which directly benefit the watershed.

Communities can choose to use any portion, or all, of these criteria when tailoring a Public Benefit Rating System to address the specific watershed issues they are facing."

Another possibility is a Shoreline Restoration Fund. A chief limitation to implementing restoration is local funding, which is often required as a match for state and federal grant sources. To foster ecological restoration of the City’s shorelines, the City could establish an account that may serve as a source of local match monies for non-profit organizations implementing restoration of the City’s shorelines. This fund could be administered by the City shoreline administrator and would be supported by a levy on new shoreline development proportional to the size or cost of the new development project. Monies drawn from the fund would be used as a local match for restoration grant funds, such as the Salmon Recovery Funding Board (SRFB), Aquatic Lands Enhancement Account (ALEA), or another source.

Shore Stewards Education

Shore Stewards are shoreline property owners and residents of waterfront communities with shared beach access who voluntarily follow 10 wildlife- friendly guidelines in caring for their beaches, bluffs, gardens and homes. These guidelines help them create and preserve a healthy shoreline environment for fish, wildlife, birds and people. This program was created to help shoreline residents feel more connected to the nearshore ecosystem because it is found that when people understand the natural processes at work on their beaches, they may play a more active, positive role in the preservation of healthy, fish-friendly wildlife habitats.

The 10 guidelines for shoreline living are:

1. Use water wisely

2. Maintain your septic system

3. Limit pesticide and fertilizer usage

4. Manage upland water runoff

5. Encourage native plants and trees

6. Know permit procedures for shoreline development

7. Develop on bluffs with care

8. Minimize bulkheads, docks and other structures

9. Respect intertidal life

10. Preserve eelgrass beds and forage fish spawning habitat

Shore Stewards was created in 2002 with grant funding by the Island County Marine Resources Committee. The pilot program was launched on Camano Island by a dedicated group of Washington State University (WSU) Beach Watchers, who wrote the resource-packed Shore Stewards Guide. Shore Stewards is now expanding to other counties of Puget Sound.

Stewardship Certification Process

The Shore Stewards program sets up guidelines for shoreline residents to preserve and enhance the shoreline environment. With a verification component, Shore Stewards could provide certification and tracking. This could be implemented as a Shoreline Tax Incentives when someone participates in the WDFW backyard sanctuary program. Since the City recognizes that there are important opportunities to improve shoreline ecological conditions and functions through non-regulatory, volunteer actions by shoreline residents and property owners it might examine the potential for property tax breaks for shoreline property owners who are actively manage their property for habitat protection or enhancement. To encourage volunteer actions that better shoreline ecological functions and values, shoreline property owners actively participating in the WDFW backyard sanctuary program or some similar program could receive, for example, a 5% credit on their City property taxes.

Resource Directory

Develop a resource list for property owners that want to be involved in restoration. Examples of grant programs that could be included are:

Landowner Incentive Program (LIP) – This is a competitive grant process to provide financial assistance to private individual landowners for the protection, enhancement, or restoration of habitat to benefit species-at-risk on privately owned lands. Check the LIP website for information about the next application cycle.

Salmon Recovery Funding Board (SRFB) Grant Programs – SRFB administers two grant programs for protection and/or restoration of salmon habitat. Eligible applicants can include municipal subdivisions (cities, towns, and counties, or port, conservation districts, utility, park and recreation, and school districts), Tribal governments, state agencies, nonprofit organizations, and private landowners. All projects require participation in the lead entity process. In the Port Townsend area, the Hood Canal Coordinating Council serves as the lead entity. Information on the program can be found in the Process Guide, available at the HCCC website at www.hccc.wa.gov.

Information on regional priorities can be found in the HCCC Salmon Habitat Recovery Strategy at the same website.

Hood Canal Community Salmon Fund – This is a partnership between the SRFB and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to provide a small grants program to implement smaller-scale projects in high priority areas, building on the HCCC Salmon Habitat Recovery Strategy and Salmon Recovery Plans.

Backyard Sanctuary Program

Encourage participation in Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife backyard sanctuary program.

14.10 Project Evaluation

When a project is proposed for implementation by the city, other agency or by a private party, the restoration project should be evaluated to ensure that the project’s objectives are consistent with those of this Restoration chapter of the SMP and, if applicable, that the project warrants implementation above other candidate projects. (It is recognized that, due to funding sources or other constraints, the range of any individual project may be narrow.)

Figure 2 (Thom 2005)

It is also expected that the list of potential projects may change over time, that new projects will be identified and existing opportunities will become less relevant as restoration occurs and as other environmental conditions, or our knowledge of them, change.

When evaluating potential projects, the following nine criteria should be considered in assessing priority (the criteria are not listed in any order of importance):

a. Restoration meets the goals and objectives for shoreline restoration.

b. Restoration of processes is generally of greater importance than restoration of functions.

c. Restoration avoids residual impacts to other functions or processes.

d. Projects address a known degraded condition.

e. Conditions that are progressively worsening are of greater priority.

f. Restoration has a high benefit to cost ratio.

g. Restoration is feasible, such as being located on and accessed by public property or private property that is cooperatively available for restoration. Restoration should avoid conflicts with adjacent property owners.

h. There is public support for the project.

i. The project is supported by and consistent with other restoration plans, such as that for WRIA 17.

The city shall develop a project “score card” as a tool to evaluate projects consistent with these criteria (for example, see the project scorecard from the Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership.

14.11 Monitoring and Adaptive Management

In addition to project monitoring required for individual restoration and mitigation projects, the city should conduct system-wide monitoring of shoreline conditions and development activity, to the degree practical, recognizing that individual project monitoring does not provide an assessment of overall shoreline ecological health. The following three-prong approach is suggested:

1. Track information using the city’s GIS and permit system as activities occur (development, conservation, restoration and mitigation), such as:

a. New shoreline development

b. Shoreline variances and the nature of the variance

c. Compliance issues

d. New impervious surface areas

e. Number of pilings

f. Removal of fill

g. Vegetation retention/loss

h. Bulkheads/armoring

The city may require project proponents to monitor as part of project mitigation, which may be incorporated into this process. Regardless, as development and restoration activities occur in the shoreline area, the city should seek to monitor shoreline conditions to determine whether both project specific and SMP overall goals are being achieved.

2. Periodically review and provide input to the regional ongoing monitoring programs, such as:

a. DNR monitoring

b. Puget Sound Ambient Monitoring Program

c. University of Washington

d. Hood Canal Dissolved Oxygen Program

e. Hood Canal Coordinating Council and associated partners

f. Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Program

Through this coordination with regional agencies, the city should seek to identify any major environmental changes that might occur.

3. Re-review status of environmental processes and functions at the time of periodic SMP updates to, at a minimum, validate the effectiveness of the SMP. Re-review should consider what restoration activities actually occurred compared to stated goals, objectives and priorities, and whether restoration projects resulted in a net improvement of shoreline resources.

Under the Shoreline Management Act, the SMP is required to result in no net loss of shoreline ecological resources. If this standard is found to not be met at the time of review, Port Townsend will be required to take corrective actions. The goal for restoration is to achieve a net improvement. The cumulative effect of restoration over the time between reviews should be evaluated along with an assessment of impacts of development that is not fully mitigated to determine effectiveness at achieving a net improvement to shoreline ecological resources.

To conduct a valid reassessment of the shoreline conditions under the schedule established by RCW 90.58.080 4(b) as currently codified or hereinafter amended by the state, it is necessary to monitor, record and maintain key environmental metrics to allow a comparison with baseline conditions.

As monitoring occurs, the city should reassess environmental conditions and restoration objectives. Those ecological processes and functions that are found to be worsening may need to become elevated in priority to prevent loss of critical resources. Alternatively, successful restoration may reduce the importance of some restoration objectives in the future.

Evaluation of shoreline conditions, permit activity, GIS data, and policy and regulatory effectiveness should occur at varying levels of detail consistent with the Comprehensive Plan update cycle. A complete reassessment of conditions, policies and regulations should be considered under the schedule established by RCW 90.58.080 4(b) as currently codified or hereinafter amended by the state. (Ord. 3062 § 3, 2011).

14.12 Uncertainty

This restoration chapter proposes project opportunities to restore shoreline conditions. The restoration opportunities included are based upon a detailed inventory and analysis of shoreline conditions. Nonetheless, exhaustive scientific information about shoreline conditions and restoration options is cost prohibitive at this stage. Additionally, restoration is experimental. Monitoring must be an aspect of all restoration projects. Information from monitoring studies will help demonstrate what restoration is most successful. Generally, conservation of existing natural areas is the least likely to result in failure. Alternatively, enhancement (as opposed to complete restoration of functions), has the highest degree of uncertainty.

This SMP does not provide a comprehensive scientific index of restoration opportunities that allows the city to objectively compare opportunities against each other. If funding was available, restoration opportunities could be ranked by which are expected to have the highest rates of success, which address the most pressing needs, and other factors. Funding could also support a long term monitoring program that evaluates restoration over the life of the SMP (as opposed to independent monitoring for each project).

14.13 Potential Funding Sources

Potential sources of grant funding for restoration opportunities on the city’s shorelines have been documented in Table 14.13-1.

|

Grant Name |

Allocating Entity |

Grant Size |

Contact |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Acorn Foundation |

Acorn Foundation |

$5,000 - 12,000 |

Elizabeth Wilcox Phone: (510) 834-2995 Email: ccounsel@igc.org |

|

Allen Family Foundation, Paul G. |

|

|

(http://www.pgafamilyfoundation.org/) |

|

Aquatic Lands Enhancement Account |

Washington Department of Natural Resources |

$10,000 – 1 Million |

Leslie Ryan Phone: (360) 902-1064 Email: leslie.ryan@wadnr.gov |

|

Audubon Washington |

|

|

|

|

Basinwide Restoration New Starts General Investigation |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

varies |

Bruce Sexauer Phone: (206) 764-6959 Email: bruce.r.sexauer@usace.army.mil |

|

Bring Back the Natives |

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation |

Variable. FY99 Grants ranged from $21,400 to 450,000 |

Pam McClelland Phone: (202) 857-0166 Email: mcclelland@nfwf.org |

|

Bullet Foundation |

|

|

|

|

City Fish Passage Barrier, Stormwater and Habitat Restoration Grant Program |

Washington Department of Transportation |

varies |

Cliff Hall Phone: (360) 705-7993 Email: hallc@wsdot.wa.gov |

|

Coastal Grant Program |

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

$5,000 - 50,000 |

Coastal Grant Contact Phone: (703) 358-2201 |

|

Coastal Zone Management Administration/ Implementation Awards |

Washington State Department of Ecology |

$19,000 - 29,000 |

Bev Huether Phone: (360) 407-7254 Email: bhue461@ecy.wa.gov |

|

Community-Based Restoration Program |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

$1,000 to 500,000 |

Chris Doley Phone: (301) 713-0174 Email: chris.doley@noaa.gov |

|

Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund |

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

$1,000 - 14,000 |

Dan Morgan Phone: (703) 358-2061 Email: Dan_Morgan@fws.gov |

|

Doris Duke Charitable Foundation |

Doris Duke Charitable Foundation |

Multi-year grants that range from $125,000 - 3.5 million |

Adrienne Fisher Phone: (212) 974-7000 Email: afisher@ddcs.org |

|

FishAmerica Grant Program |

FishAmerica Foundation |

varies |

Johanna Laderman Phone: (703) 519-9691 Email: jladerman@asafishing.org |

|

Five-Star Restoration Program |

Environmental Protection Agency |

$5,000 - 20,000. Subgrants average $10,000 |

John Pai Phone: (202) 260-8076 Email: pai.john@epa.gov |

|

FMC Corporation Bird and Habitat Conservation Fund |

FMC Corporation and The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation |

varies |

Peter Stangel Phone: (404) 769-7099 Email: stangel@nfwf.org |

|

Forest Legacy Program – Washington |

U.S. Forest Service, Washington Department of Natural Resources |

varies |

Brad Pruitt Phone: (360) 902-1102 Email: brad.pruitt@wadnr.gov |

|

Habitat Conservation |

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Coastal Program |

varies |

Sally Valdes Phone: 703-358-2201 Email: sally.valdes@fws.gov |

|

Hugh and Jane Ferguson Foundation |

Hugh and Jane Ferguson Foundation |

$2,000 - 7,500 |

Therese Ogle Phone: (206) 781-3472 Email: OgleFounds@aol.com |

|

Landowner incentive program |

Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife, Lands Division |

up to $5,000 for small grants; others up to $50,000 |

Ginna Correa or Jeff Skriletz Phone: (360) 902-2478 or (360) 902-8313 http://wdfw.wa.gov/lands/lip |

|

Matching Aid to Restore States Habitat (MARSH) |

Ducks Unlimited |

varies |

Ducks Unlimited Phone: (916) 852-2000 Email: conserv@ducks.org |

|

Migratory Bird Conservancy |

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation |

$10,000 - 60,000 |

Peter Stangel Phone: (404) 769-7099 Email: stangel@nfwf.org |

|

Native Plant Conservation Initiative |

Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service |

$10,000 - 50,000 |

Caroline Cremer Phone: (202) 857-0166 Email: caroline.cremer@nfwf.org |

|

Nonpoint Source Implementation Grant (319) Program |

Environmental Protection Agency, Washington State Department of Ecology |

varies |

Aleciea Tilley Email: atill461@ecy.wa.gov |

|

North American Wetlands Conservation Act Grants Program |

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

$100,000 - 1 million, small grants capped at $50,000 |

Bettina Sparrowe Phone: (703) 358-1784 Email: r9arw_nawwo@fws.gov |

|

Pacific Grassroots Salmon Initiative |

National Fish & Wildlife Foundation |

$5,000 - 100,000 |

Anna Weinstein Phone: (415) 778-0999 Email: weinstein@nfwf.org |

|

Planning/Technical Assistance Program |

Bureau of Reclamation |

varies |

Dave Nelson Phone: (503) 872-2801 Email: drnelson@pn.usbr.gov |

|

Puget Sound Action Team Public Involvement and Education fund |

Puget Sound Action Team |

|

http://www.psat.wa.gov/Programs/Education.htm |

|

Puget Sound Program |

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

varies |

Mary Mahaffy Phone: (360) 753-7763 Email: mary_mahaffy@fws.gov |

|

Puget Sound Wetland Restoration Program |

Washington State Department of Ecology |

Technical Assistance |

Richard Gersib Phone: (360) 407-7259 Email: rger461@ecy.wa.gov |

|

Regional Fisheries Enhancement Groups |

Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife |

$10,000 - 40,000 |

Kristi Lynett Phone: (360) 902-2237 Email: lynetksl@dfw.wa.gov |

|

Salmon Recovery Funding Board |

Interagency Committee for Outdoor Recreation |

varies |

Rollie Geppert Phone: (360) 902-2636 Email: Salmon@iac.wa.gov |

|

Section 204: Environmental Restoration Projects in Connection with Dredging |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

75% of total project modification costs |

Mona Thomason Phone: (206) 764-3600 Email: mona.j.thomason@usace.army.mil |

|

Section 206: Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Program |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

65% of total project implementation cost |

Martin Hudson Phone: (503) 808-4703 Email: martin.hudson@usace.army.mil |

|

Transportation Environmental Research Program (TERP) |

Federal Highway Administration |

$20,000 - $50,000 |

Michael Koontz Phone: 410-962-4586 Email: michael.koontz@fhwa.dot.gov |

|

Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) |

Washington Department of Transportation |

varies |

Shari Schaftlein Phone: (360) 705-7446 Email: sschaft@wsdot.wa.gov |

|

Washington State Ecosystems Conservation Program |

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

$500 - 26,000 |

Rich Carlson Phone: (360) 753-5829 Email: rich_carlson@fws.gov |

|

Wetland Protection, Restoration, and Stewardship Discretionary Funding |

Environmental Protection Agency |

$5,000 - $20,000 |

Christina Miller Phone: (206) 553-6512 Email: miller.christina@epa.gov |

More detailed information about eligibility may be obtained from the contact identified for the funding source.

14.14 Restoration Glossary

Abiotic: Nonliving, such as environmental factors including light, temperature, and atmospheric gases.

Biotic: Produced or caused by living organisms or having to do with life or living organisms.

Disturbance: Any relatively discrete event in time and space that disrupts or alters some portion of an ecosystem. Disturbances are important factors that affect the character and state of ecosystems. Examples from nearshore ecosystems include: